Memory + Perception + Phenomenology

Memory + Perception + Phenomenology

By Anna Ehrsam

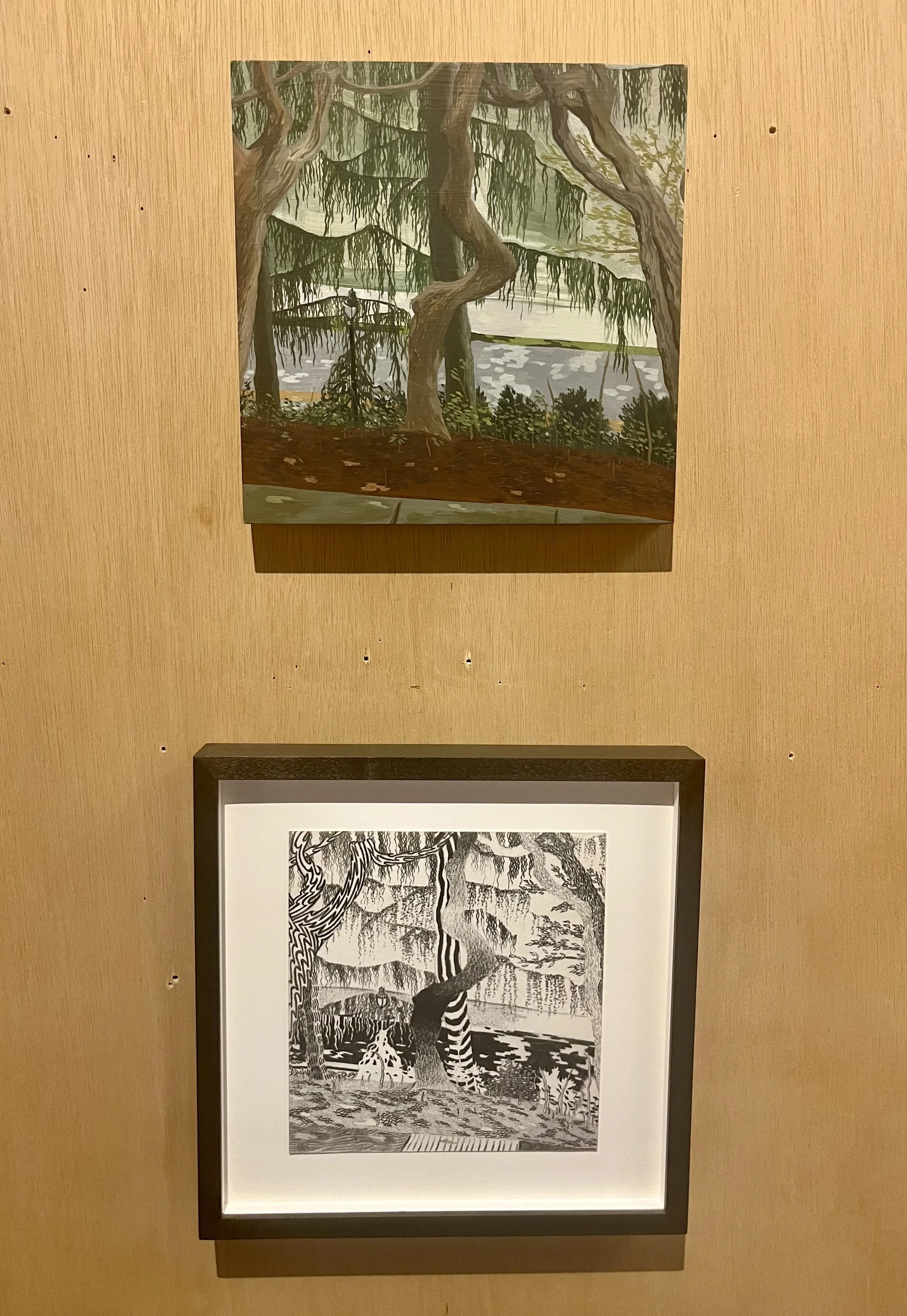

Envisaged Landscapes

Paintings + Drawings by Chris Schade

May 2 – June 4 Gallery Very

Artist Gallery Talk: Saturday, May 10, from 2:30 to 3:30 PM

Closing Reception: Saturday, May 31, from 2 to 5 PM

Gallery VERY is open on Saturdays from 2 to 5 PM and by appointment: galleryvery@gmail.com

Location: 59 Wareham Street, Boston, MA 02118

Chris Schade possesses a strong desire to communicate something of our shared realities in an ever-shifting temporal and spatial flux. His work asks how we can hold onto and create shared meaning.

Schade constructs complexities out of the ordinary, the everyday landscape, and lived experience. He questions the fixed nature of reality, preferring instead a shifting perspective, one that resists being pinned down. He plays optical tricks and engages the viewer in the pleasure of looking, without demanding interpretation. The viewer’s subjectivity is essential, it completes the viewing process and the work itself. These are deeply philosophical paintings made with great technical skill, yet they open into something more expansive, a breakdown and rebuilding of meaning through memory, observation, and recontextualization.

Schade integrates memory, objectivity, symbolic meaning, and slippage into an exploration of the nature of reality. He began painting from observation in 1997 to learn how to depict deep space through atmospheric perspective. This approach revealed the subtlety of local color, the temporality of shifting light, and the overwhelming complexity of nature. Rather than simply looking at the subject, he became part of it, embedded in something inherently vast and greater than himself.

In Perceived Landscapes, Schade uses plein air methods to root his work in shared visual reality. This traditional technique provides a recognizable structure, an entry point from which he can explore, exploit expectation, and inject his own idiosyncratic interests.

These outdoor works became the compositional source material for his Envisaged Landscapes, created later in the studio. The process initiates a psychological and perceptual transformation, anchored in shared reality, yet ultimately destabilizing visual cues to provoke new forms and meanings.

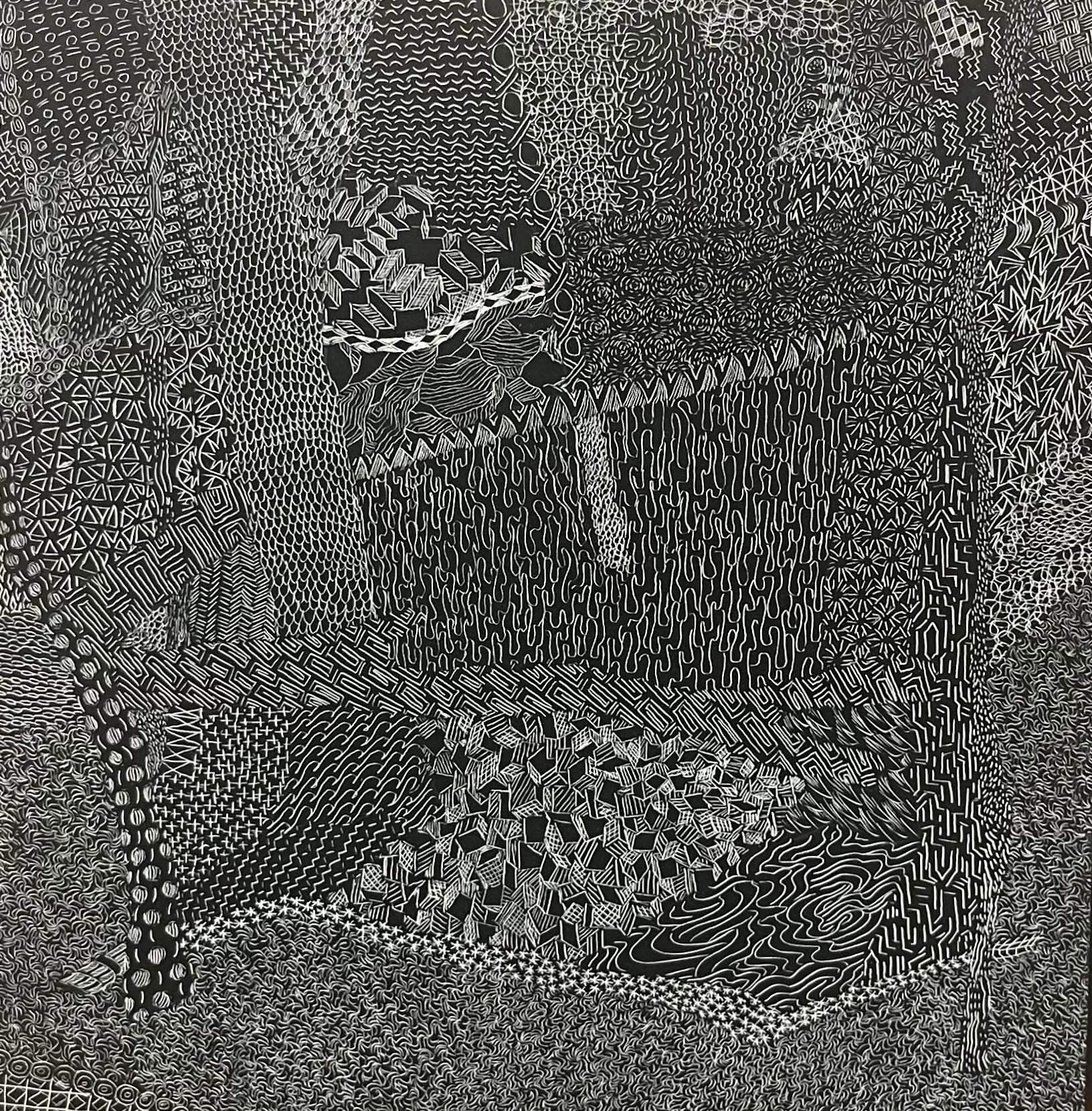

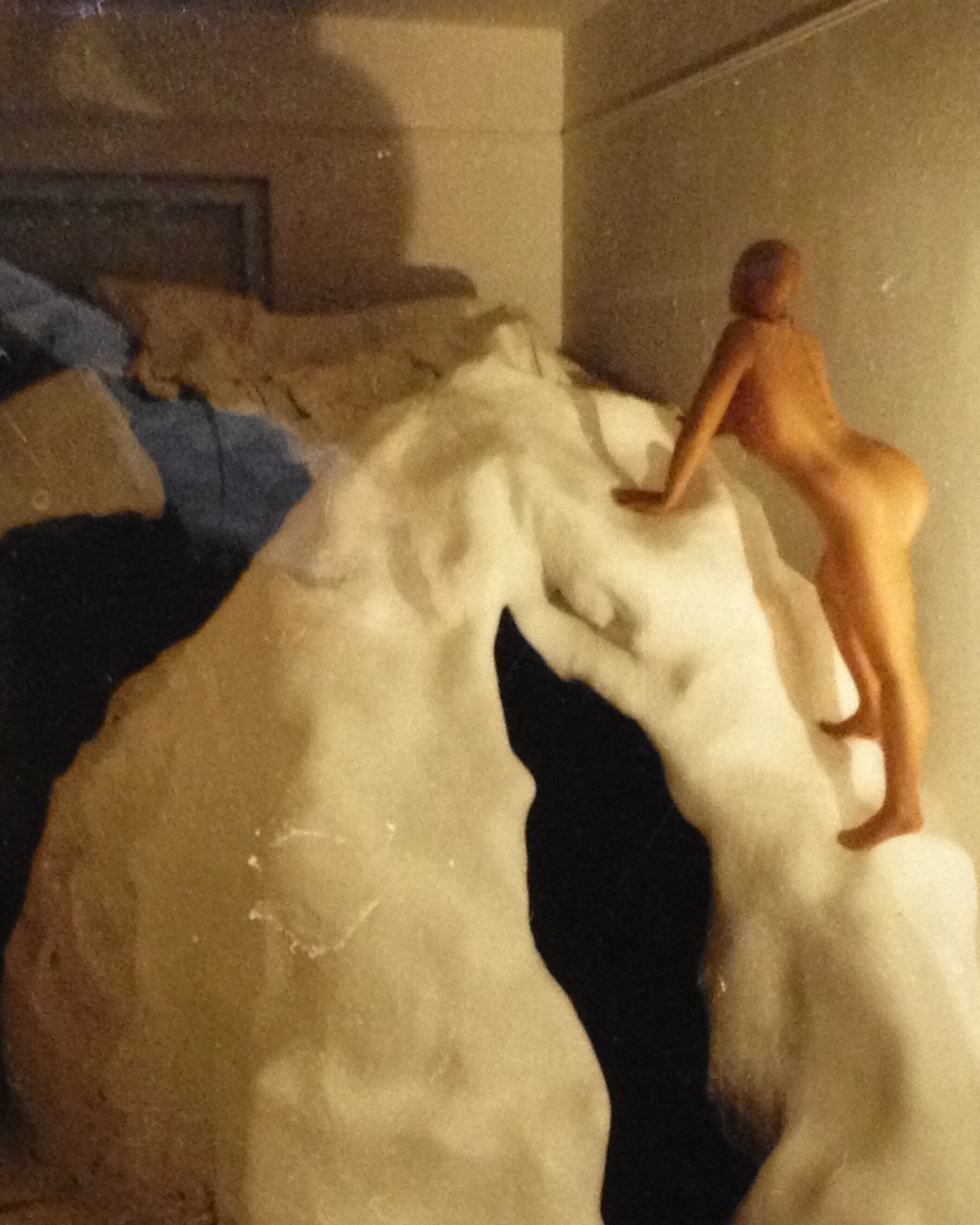

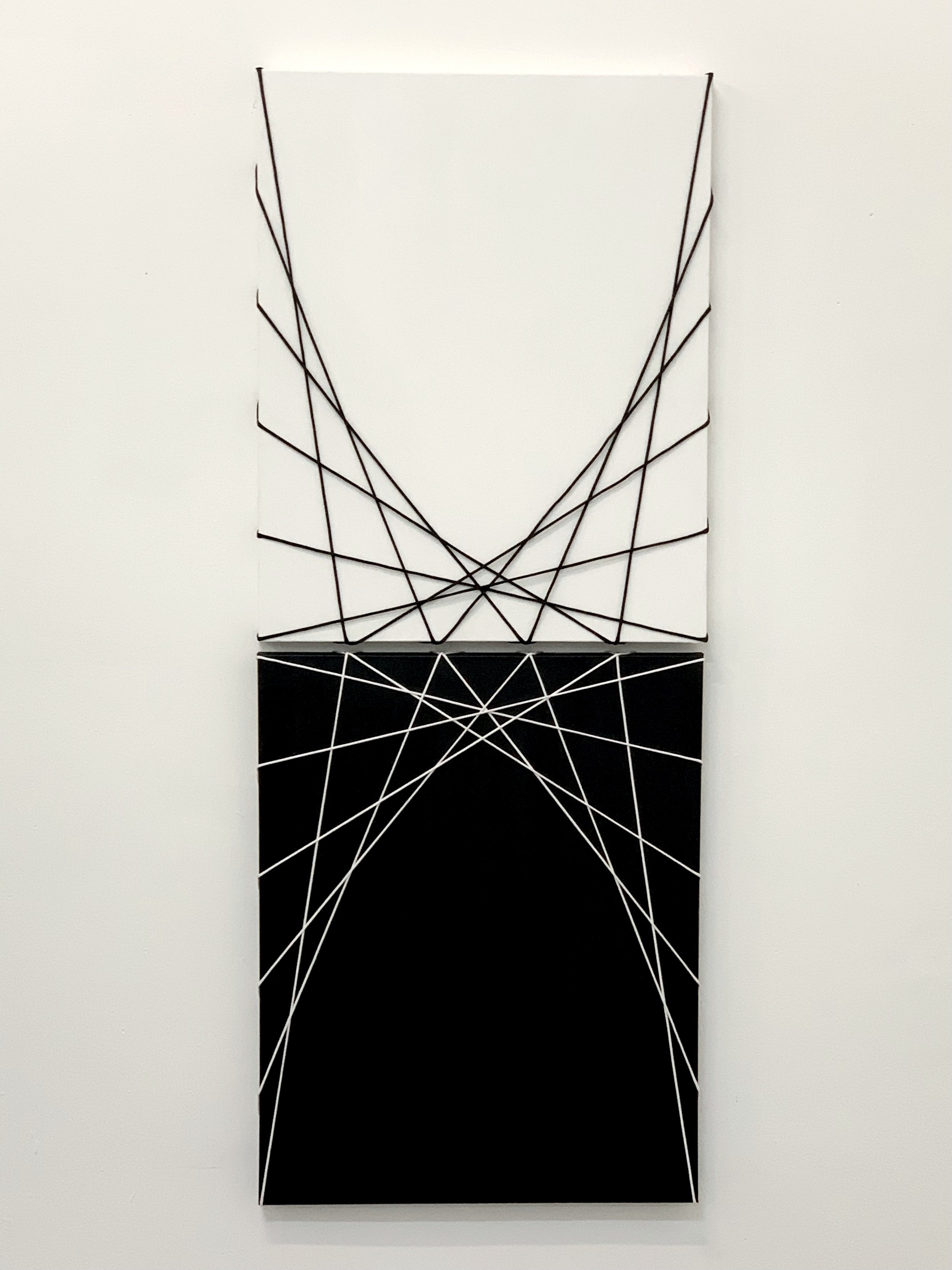

Schade’s paintings are not static images, but rather events, phenomenological encounters where lived and imagined realities converge in unexpected and intricate ways. The landscapes shift, morph, and evolve into complex accumulations of densely networked information. His mastery is evident in the way he deftly composes formal elements into a cohesive whole of great subtlety and complexity.

The compositions, formed through a synthesis of site-specific and invented color schemes, morphing forms drawn from both the natural and built environments, and infinite variations of pattern, coalesce into reinterpreted and reimagined visions of reality and imagination. These elements are not merely formal devices, they function symbolically, actively destabilizing perception. In his recent work, Schade transposes observed colors into deliberately dissonant or "incorrect" contexts, generating dream-like, surreal atmospheres that hover between familiarity and estrangement. In doing so, his paintings elude straightforward recognition, foregrounding instead the fluid, slippery nature of memory and perception.

Site-specific color palettes generate purple trees, red grass, and kaleidoscopic skies. The influence of the Fauvists, with their incongruent color, is present, as is a sense of disorientation drawn from memory rather than realism. These are not imagined landscapes, they are observations shifted out of alignment, closer to psychological truth than visual fact.

Teaching is central to Schade’s practice. His commitment to clarity and communication reflects a broader desire to connect across cultures and differences. His upbringing was rich in language and layered with complexity, his mother taught Spanish and his father Latin American literature. These backgrounds, combined with his brother’s struggle with schizophrenia, created a household of play, invention, and perceptual multiplicity.

Growing up between Austin, Texas, and Quirihue, Chile, in a bilingual and bicultural home, Schade experienced landscape, language, and identity as inherently fluid. His father translated Latin American literature, his mother was an immigrant and an academic. Communication was flexible, often involving invented words or hybrid languages.

His brother Philip, who had schizoaffective disorder, influenced Schade’s view of perception and meaning. Philip often saw the world symbolically, breaking from normative understandings. The artist’s exploration of reality is deeply tied to this early familial experience, its tensions, its imagination, and its emotional range.

Concepts such as confabulation, the phenomenon of false memory held with conviction, and anosognosia, a lack of insight, are embedded in Schade’s experimentation. His work confronts how we remember, misremember, and perceive. “Déjame tener mis ilusiones” (“Let me have my illusions”), Matilde Schade, the artist’s mother, would often say. That phrase resonates throughout the work.

Schade’s use of pattern, camouflage, and pareidolia, where perception invents meaning, creates deliberate ambiguity. Influenced by his wife Zoe’s work on pattern theory, Schade uses repeating lines and shapes that dissolve rather than reinforce object reality. Specific patterns may recur in a single space, but they never repeat across the canvas, heightening a sense of the unknown.

Seriality also plays a structural role in many of Schade’s paintings. Like Monet’s Haystacks or Rouen Cathedral series, his repeating compositions allow for variation over time, exploring the instability of perception. Form remains, but meaning mutates.

Schade avoids photography and digital mediation. He prefers direct, lived experience, what he calls a “record of perception in space and time.” The accumulation of marks, colors, changing light, and the body’s presence create paintings that embody lived existence.

Phenomenology, the study of human experience from a first-person perspective, runs throughout Schade’s practice. He bridges subjective and objective realities, showing how meaning and perception can be both fleeting and grounded.

As Schade says, “Ultimately, I’m interested in how we visually perceive and how and why we believe what we do. I want to know what our shared reality is, what are its limits, and what visually leads to recognition or dissolution of form.” His work challenges us to tune our perceptions, to cultivate sensitivity to how we see, feel, and believe. By holding difference, he creates space for a more nuanced and collective understanding of reality.