MICHAEL ZANSKY: BOSCH FOR TODAY BY DONALD KUSPIT

MICHAEL ZANSKY: BOSCH FOR TODAY

BY DONALD KUSPIT

This Tabernaculum Dei cum hominibus, to quote from the inscription on the frame, is poised like an enchanting vision above a spectacle as horrifying as any canto in Dante or Milton. A barren earth and angry sea give up their dead. A youthful, brilliantly armored St. Michael, sword drawn and legs astraddle, controls the Spectre of Death, a giant skeleton that seems to rush toward the beholder in head-on foreshortening and stares at us with sightless eyes. Its bat wings, inscribed with the words CHAOS MAGNV and VMBRA MORTIS are stretched throughout the picture so as to separate, most literally, the realm of light from the “mist of darkness,” and the droves of the Damned plummet headlong into the pit to fall prey to hideous demons who merge with their victims in a seething mass of tortured confusion. To compare this evocation of the Abyss with the phantasmagorias of Jerome Bosch is saying too much and too little; conceived

by a mind profoundly sane and optimistic, its horrors are not dreamt but seen. Bosch’s Paradise has fundamentally the same weird, nightmarish quality as his Hell. — Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting, commenting on Hubert and/or Jan van Eyck’s Last Judgment, ca. 1430–35.

Edifying—and horrifying—religious literature (for example, the Ars moriendi and such accounts of Hell and Purgatory as the Visio Tundali) must also have played its part in Bosch’s intellectual life, together with popular science, Rabbinical legend, the inexhaustible storehouse of native folklore and proverbial wisdom, and, above all, orthodox Christian theology….and I am profoundly convinced that he, a highly regarded citizen of his little home town and for thirty years a member in good standing of the furiously respectable Confraternity of Our Lady, could not have belonged to, and worked for, an esoteric club of heretics, believing in a Rasputin-like mixture of sex, mystical illumination and nudism, which was effectively dealt with in a trial in 1411….Jerome Bosch was not so much a heretic as one of those extreme moralists who, obsessed with what they fight, are haunted, not unpleasurably, by visions of unheard-of obscenities, perversions and tortures….he may have been a case for psychoanalysis, but not for the Inquisition. — Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting.

It is undoubtedly unusual that plays teach first by learning themselves, that the involved persons and their actions are turned upside down in a questioning and investigating way. And yet, there is already an open form in all dramas, where human beings and situations are shown particularly in their permanent contradictions. — Ernst Bloch, “The Stage Regarded as a Paradigmatic Institution and the Decision within It.”

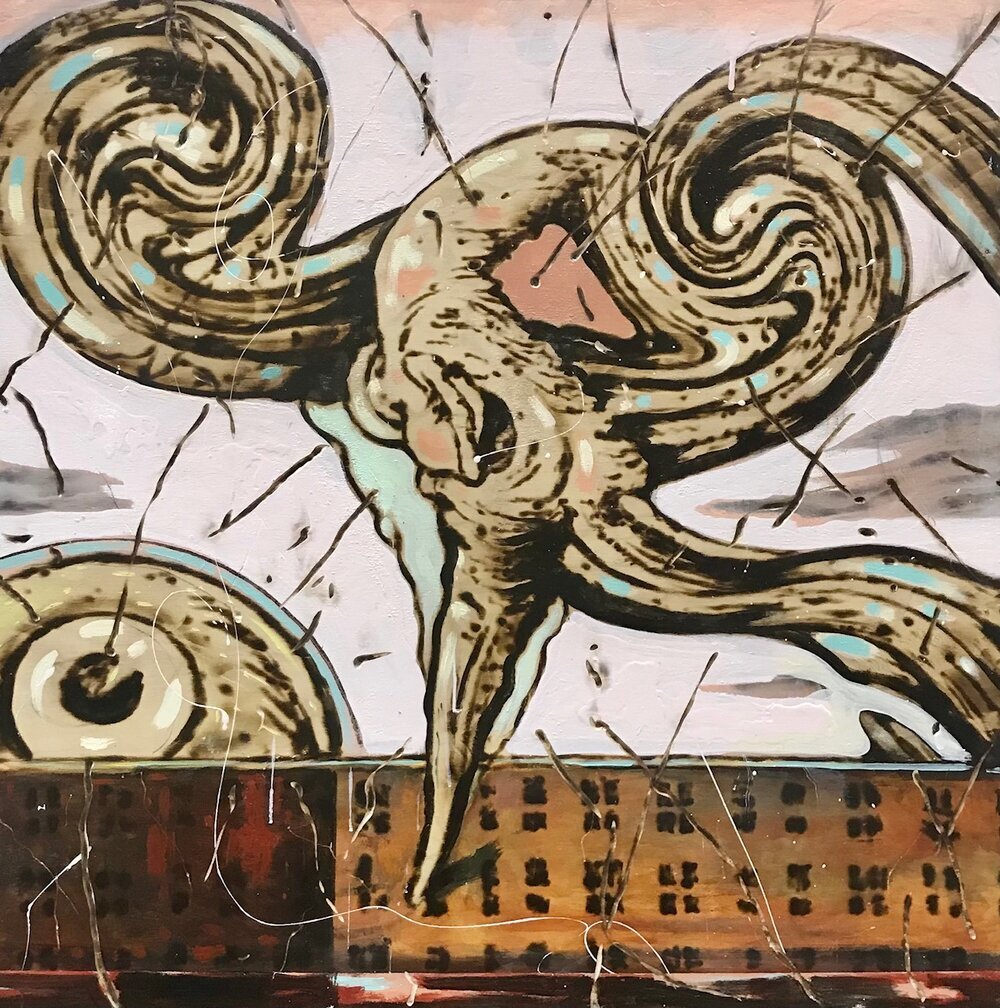

Michael Zansky’s work as the Lead Set Painter for the popular television series Law and Order: Special Victims Unit seems to me one of the keys to his other, more bizarre, not to say mordantly esoteric work, particularly his theatrical masterpiece Giants and Dwarfs, 1990–2002, a panoramic installation on the grand scale and in the grand manner of theatrical Old Master frescos. The grain of the wood in which the visionary images are forcefully carved or carefully etched—they seem immutably embedded in the surface, like fossils, even as they seem to erupt from the impenetrable depths beneath it, with sudden insistence—gives them a certain expressionistic flavor and intensity, but they remain hypnotically intact, their raw tactility serving their unnerving meaning rather than an aesthetic end in itself.

One cannot help thinking of Munch’s early woodcuts and van Gogh’s late paintings, both of which have a similar hallucinatory character; the grainy wood and grainy painterliness conveying the excited emotions that animate the images so that they seem uncannily absurd yet oddly descriptive. Giants and Dwarfs, also expressively distorted and insidiously empirical, is Zansky’s signature piece, as Munch’s The Scream, 1893, is his, and van Gogh’s Self-Portrait, 1888, is his. All three works convey the artists' experience of himself—his contradictory sense of himself—which is why outwardly they appear strange, suggesting the artists felt strange to themselves. This is all the more so in Giants and Dwarfs, where the figures, most absurdly inchoate, some clearly animals, seem to symbolize a self that is a mystery to itself. Like Munch and van Gogh, Zansky—and he is clearly their peer—seems to feel like a a social outsider, like a “stranger on the earth,” the title of Albert E. Lubin’s masterful psychological biography of van Gogh.

Doubly estranged, from society and himself, Zansky cannot help but feel isolated and involuted: his peculiarly warped figures are much more expressively profound, not to say emotionally shocking, than Munch’s and van Gogh’s more plausibly human figures. Zansky's warped figures seem to be twisted in on themselves, as though seen in a distorting mirror, giving them monstrous shapes with a certain affinity to the incomprehensible anamorphic form of the death’s-head in Holbein’s The French Ambassadors, 1533. In unfamiliar anamorphic form, the death’s-head represents the unconscious truth; seen from the “right” perspective, it comes into clear focus, losing its enigmatic appearance—but gaining shocking meaning—in a jolt of recognition. The tension between the unconsciously felt, deformed, unnatural, unknown and the

consciously perceived, naturally formed, clearly known is greater in Zansky’s work than in Munch’s and van Gogh’s, making it more threatening and insidious. I will argue that it has greater affinity with the ancient imagery of the grotesque, traceable to Roman decorative style— Zansky acknowledges the influence of the grotesque mask in a mosaic of the Casa Del Fauno in Pompeii—and evident in, more extreme, absolute, confrontational form, in Holbein’s death’shead, than with the tamer modern grotesque, evident in Munch’s and van Gogh’s mildly deformed figures. The grotesque is less of the essence of their art than it is of Holbein’s grotesquely distorted death’s-head and Zansky’s grotesquely distorted figures. In Zansky’s Age of Iron, 2012, there seems more than an incidental kinship between them: the grayish shape hovering in the airless space has the same misshapen appearance as Holbein’s anamorphic skull, suggesting that Zansky is unconsciously quoting it.

The ancient grotesque mask is an uncanny fusion of the comic and tragic masks of ancient theater, a paradoxical integration of opposites suggesting that it is hard to know whether to laugh or weep at life. The grotesque suggests that one is as good as the other—that laughter quickly becomes weeping and vice versa. Wearing the grotesque mask as his inner face, Zansky is both Democritus, the laughing philosopher, and Heracleitus, the weeping philosopher. Heracleitus argued that all is in metamorphic flux and thus tragically unstable, and Democritus argued that all is reducible to elemental matter and thus comically stable; Zansky’s art deals with the metamorphic flux of elemental matter. The bizarre figures in such works as Thought Transference, Valley of the Kings, and Cipher 5, all 2009–10, are peculiarly comic and tragic at once. The figures of Munch and van Gogh are only pitiable.

In Holbein, the meaning of the death’s-head is defensively repressed, even denied, by distorting its appearance into a grotesqueness so complete and radical that it becomes unrecognizable, so that it doesn’t seem to belong in the picture of The French Ambassadors. It seems “incorrect” and a “mistake,” not to say “wrong-headed” and “thoughtless,” compared to the men's “unmistakable,” “correct” appearance and “right-headedness”; they are men of reason and culture, as the objects accompanying them suggest). The obscurity of the totally distorted skull makes it peculiarly haunting, as though insinuating it into our unconscious. To use Freud’s distinction, in grotesquely distorted anamorphic form, Holbein’s skull is the manifest content of a terrifying dream; seen from the “correct” point of view when one is awake, one understands its meaning, which is the dream’s latent content. Death is unrepresentable, the anamorphically distorted skull suggests—a skull that has become an absurd abstraction, so estranged from its appearance that it seems to have no reality, a skull that seems more immaterial than material, a formless mirage that seems to have no meaning, an empty blur invading the clarity of the scene like a cancer—but undistorted and “interpreted,” the skull represents and materializes death.

One must make the same revolutionary change of point of view to grasp the meaning of

Zansky’s distorted figures; one does not have to change one’s point of view to understand Munch’s and van Gogh’s figures. They are instantly comprehensible; Zansky’s figures must be interpreted to be fully comprehended. Munch’s and van Gogh’s figures look normal, realistic, and familiar compared to Zansky’s abnormal, unrealistic, unfamiliar dream figures. Munch and van Gogh are not deeply shocking, however much they afford the so-called shock of the new. In contrast, like Holbein’s anamorphic skull, Zansky’s grotesque figures, rooted in age-old art, shock us to the core of our being. They, too, have the ugliness of death, seem like death perversely incarnate, together forming a sort of macabre dance of death. If life is beautiful, then death is ugly, and the grotesque is anti-life ugliness epitomized: what the philosopher Francis Bacon called the “something strange” that infects beauty and disrupts its harmony, is death. Zansky is a master of strangeness more than Munch and van Gogh ever were. Zansky’s capacity for strangeness makes him the greatest master of the grotesque since antiquity—even

greater than Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, and the other Francis Bacon, the modern masters of grotesque expression.

In the Renaissance, the goal of art was grace, as Vasari wrote, stating that the “divine

Michelangelo Buonarroti” realized it as no other artist had before him. In modernity, the goal of art was the grotesque, making its first dramatic appearance in the bizarre figures pictured in Redon’s Symbolist portfolio of prints, In the Dream, 1879. They were officially the first dream, surreal imagery, and for some art historians a precedent for the art of the insane that became influential in the twentieth century. The grotesque is the opposite of grace—indeed, a fall from grace, the “disgrace” Adam and Eve suffered when they sinned, bringing with it the feeling that their bodies, beautiful in paradise, had become peculiarly ugly and unsightly. Zansky's Giants and Dwarfs is a perverse update of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, inviting ironical comparison with it, all the more so because it is as overwhelming and intimidating. Michelangelo’s Last Judgment turns the Chapel into a kind of theater in the round, like Zansky’s Giants and Dwarfs. For Zansky the ceiling is a religious “comic strip of fifteenth-and sixteenth-century thought” about “how the universe is created,” which he replaces with a scientific comic strip of nineteenth-and twentieth-century thought about how the universe is created. Zansky is

as great a master of the devilishly grotesque as Michelangelo was of the divinely graceful. In Zansky’s godless universe, nature is in perpetually amorphous process, obscenely chaotic evolution, with no Adam and Eve on the scene, and certainly no garden of paradise. As such, it is profane, ugly, and grotesque compared to Michelangelo’s sacred, beautiful, harmonious universe, created by the grace of God for man, who was his greatest and most beautiful creation. Zansky shows us a universe fallen from grace, like the abysmal hell of Van Eyck and Bosch. In Bosch, hell is ironically conflated with heaven, for his paradise is the opposite of what it seems to be, like the famous image of the false or anti-Christ, which is a Christ look-alike but seductively naked, in his Adoration of the Kings, ca. 1510. In Zansky’s hell, the devils don’t have to disguise themselves as angels. For Zansky the evolutionist man is descended from beasts, which abound in Giants and Dwarfs, overgrown and monstrous creatures in a primeval jungle. Man is himself half-beast, as the devil is in religious iconography. The comparison of Bosch and Zansky announces another significant difference between the art of Munch and van Gogh’s and that of Zansky’s. Munch’s and van Gogh’s works look forward to expressionistic signature painting, which involves what Ernst Gombrich called submission to “the anarchic tendencies of the unconscious”—more particularly “the instinctive drives” that are “the most primitive layer of our mental life.” Munch and van Gogh's works look forward to the beginning of twentieth-century avant-gardism, heavily influenced by primitive art, as Gombrich remarks, in the hope that what Gauguin called its “savagery” and “barbarism” could “rejuvenate” art. (By the nineteenth century, classical beauty, which had inspired art since the Renaissance, seemed overripe and academic, not to say shop-worn and devitalizing—all too “slow” for what Baudelaire called “the rapidity of movement” in modern life.) Zansky’s work, however primitivist its technique sometimes seems, looks backward to traditional eschatological painting, with its superego character. Adam and Eve gave in to their sexual instincts and were punished by God the superego, and Zansky’s instinct-driven figures are punished in primeval hell, like those of Bosch.

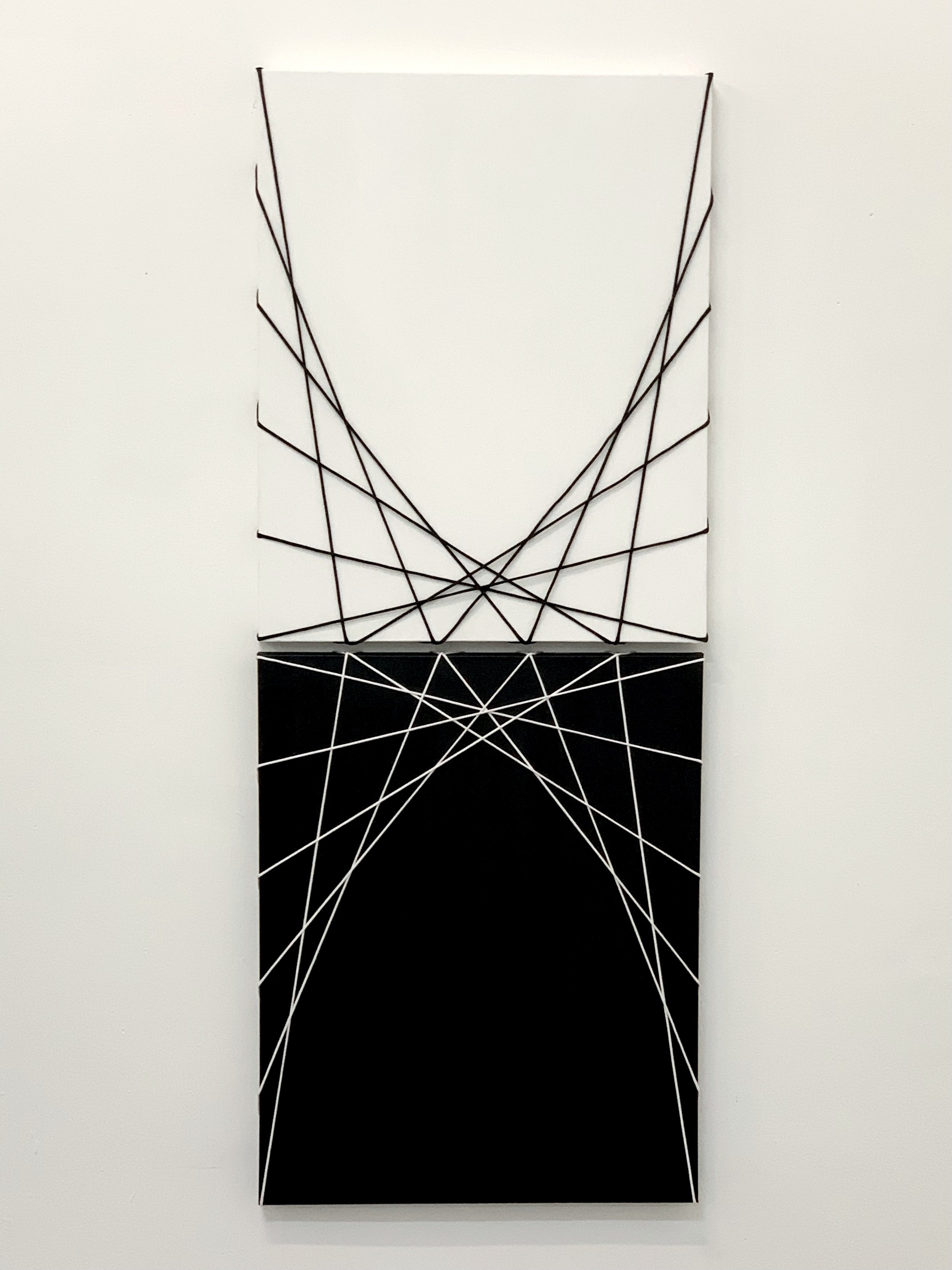

The decadence and bankruptcy that overtook classicism after a run of nearly four centuries— from, say, the remark about the “many and fine godly arts…of the virtuous ancients” with which Alberti began his 1435 treatise “On Painting,” to the assertion that “antiquity has not ceased to be the great school of modern painters” with which David began his explanation of his 1800 painting The Sabines—overtook modernism, with the development of postmodern “postart,” in less than a century. The boundary between everyday life and imaginative art became blurred; the mindless expression of primitive instinct became a cliché; “outsider” avant-garde art became “insider” establishment art; once proudly independent art became dependent on institutions for its legitimacy, even identity. What had once seemed like true art—full of “spontaneous gesture” and “personalized idea” and as such an expression of what the psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott calls the “true self”—had now become “false art,” on the model of Winnicott’s “false self,” a compliant cog in the socioeconomic machinery of art. What Gombrich called the “permanent revolution” became retardataire; what was once forward-looking—recklessly unconventional— became conventional and routine. The avant-garde claimed to renew art, but it became stifling. With the avant-garde now the rearguard, to “break with tradition” (including the now traditional avant-garde), which was supposedly a creative act and a sign and proof of originality, an artist had to invoke the traditional. What Baudelaire called the “great tradition” seemed to rise from the dead like Lazarus.

Museum art, as Clement Greenberg called it, no longer seemed like a dead end; some artists, who rejected it to look avant-garde, returned to it for creative inspiration after their “breakthrough.” They realized that breakthroughs are short-lived and unsustainable (by definition); the question remains: how does one make an art that has staying power—art for the long term, like the art of the great tradition, not art for the short term, like avant-garde art, which quickly became what Greenberg called novelty art. They intuitively realized that “it is not possible to be original except on a basis of tradition,” as Winnicott wrote, suggesting that avant-garde originality stands on shaky ground because it repudiates tradition. They learned the hard avant-garde way that without the “facilitating environment” of tradition—the constant nourishment and support of tradition—art eventually withers on the vine. They watched the avant-garde revolution against traditional art become a repressive reign of terror. For them tradition became a treasure chest rather than reified history, true art rather than false art, the embodied living spirit rather than the dead letter of art. Especially because, viewed in art historical perspective, installed as one art among the many in the universal museum of art, the avant-garde tradition of the new no longer looked as “great” as its “breakthroughs” initially made

it seem. However, it did develop many “great” new methods of making art. In avant-garde art technical innovation became an end in itself—and became confused with originality, which involves what Winnicott calls “primary creativity” and “creative apperception”—but it does not guarantee what Greenberg dismissively called the “spirituality” and emotional depth of the great Old Masters.

As the philosopher T. W. Adorno wrote, modern art—and he was a devotee and advocate of it— may claim to “will what has never existed before, but…the shadow of the past looms over everything.” Past art—including the art of the modern past—informs Zansky’s “dream imagination,” to use Freud’s term, even as it is concerned with processing the present. Just as Renoir looked to Rubens’s paintings for inspiration and support, Epstein to Michelangelo’s sculptures, and Soutine to Rembrandt’s paintings, Zansky looked to Dürer’s prints; like Dürer, he is a post-avant-garde artist, fusing traditional and avant-garde ideas of art—more precisely, using modernist means to address traditional spiritual issues. Zansky realizes that the unconscious alone can no longer make the artist magically creative, as Redon thought it could; the artist must now be fully conscious—of the encyclopedic richness of art history as well as of his own and society’s complexity—to be meaningfully creative. The avant-garde tradition dead-ends in pure abstract art; it is the climax of what has been called the religion of art that developed in the nineteenth century. The worship of art replaced the worship of God, as though the creation of art was the same as the creation of life, with art finally essentializing itself as though it were more important than existence. Whereas, the great tradition was concerned with the comprehensive representation of the “all too human,” with all its paradoxes and problems. I am arguing that Zansky ambitiously engages the great tradition—indeed, that his art belongs to the great tradition—using and ingeniously fusing a variety of modern and traditional, abstract and representational, modes of artistic expression. The tondos, 2011–12 are an eloquent example—to restore what Baudelaire called the “majesty” of art—confirming that for Zansky the all too human is more important than narcissistically pure art.

It has been said that Zansky is a Surrealist. If so, his Surrealism is heavily indebted to the

Surrealism of Bosch’s religious painting, with its spiritual existentialism. Bosch has been said to be more Surrealist than the modern Surrealists, but there is a crucial difference. Following Breton, they were indifferent to “any control exercised by reason” and “any aesthetic or moral concern,” relying entirely on what Breton, in his 1924 Surrealist manifesto, called “pure psychic[ological] automatism.” (He took the term, without acknowledgement, from the title of Pierre Janet’s 1888 book about it; Janet was a founding father of modern psychiatry.) Automatist expression is supposedly free expression, for Breton modeled on Freud’s idea of free association, which, as Freud ironically noted, is not free but unconsciously determined. Both expressionist signature painting and surrealist dream painting are rooted in automatism, which is a way of making the unconscious conscious, of articulating inarticulate sensations and

feelings—those that are seemingly irrational and unaesthetic and that are beyond good and evil. It is throwing all caution and inhibition to the winds in the name of rootless “self-expression." But Bosch’s paintings, like Zansky’s works, are rationally conceived, imaginatively aesthetic, and above all concerned with good and evil. And, one might add, more carefully crafted, not to say better made, than expressionist and surrealist paintings. Zansky’s art is urgently moral: his Giants and Dwarfs belong in Bosch’s Hell.

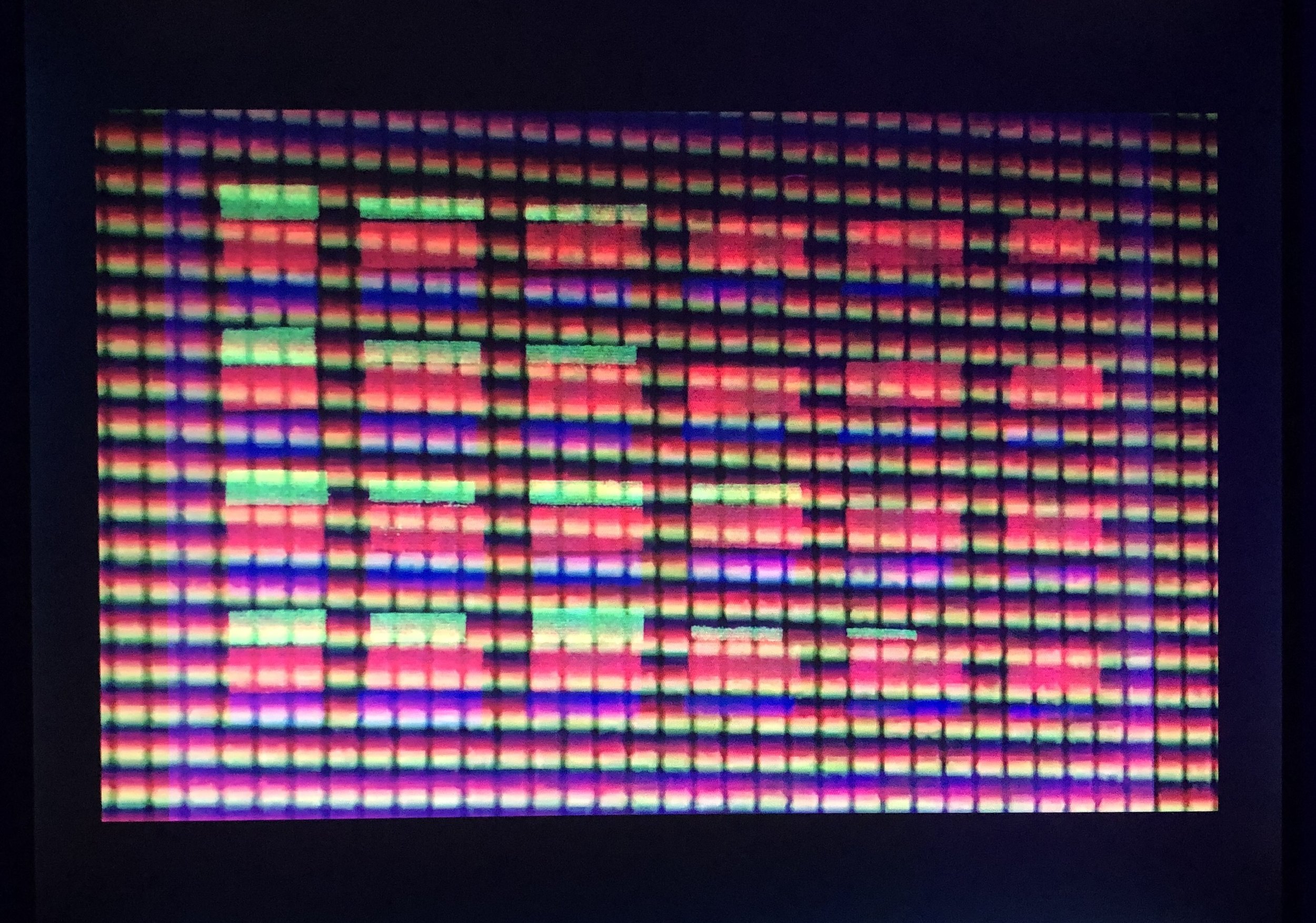

Law and Order: Special Victims Unit is also urgently moral: it too is a morality play, if less satiric, fantastic, and formulaic than Bosch’s and Zansky’s. It deals with criminals, just as Bosch and Zansky deal with sinners; the subjects of both the TV show and the artists' works have let their instincts determine their behavior, which is why they must be punished by the superego, represented by the God in the Last Judgment by Bosch, the police and judge in Law and Order: Special Victims Unit, and, I will argue, by Zansky’s American Panopticon, 2013. It is his climactic representation of hell on earth—a technological/bureaucratic society in which we are under constant surveillance by a mechanical eye (not exactly the mind’s eye). An artificial eye as all-seeing as God’s eye and as sharp as St. Michael’s sword. A public eye that also watches over us wherever we are, that sees whatever we do, and that judges and punishes us if we do something bad. An eye that makes us feel safe by controlling us—Big Brother’s eye enforcing blind obedience. We internalize and idolize the technologically, bureaucratically rational administrative eye of the collective superego, as though it can save us from our irrational instincts, as though technology/bureaucracy can tame the beast in us. The eye is a nightmare from the indignant point of view of technologically/bureaucratically self-righteous society, as the nightmarish forms it has in Zansky’s Giants and Dwarfs makes clear.

It is worth noting that Law and Order: Special Victims Unit deals with crimes against nature— sexual crimes—which are also represented in Bosch’s Triptych of the Garden of Earthly Delights, ca. 1505–10. It depicts a variety of perverse sexual acts, suggesting that the garden is an obscene hell—earthly delights are not exactly heavenly delights—bringing to mind Panofsky’s observation that Bosch’s heaven and hell are equally “nightmarish.” Their similarity suggests their interchangeability. Similarly, in Zansky’s art the irrational unconscious, with its obscene instincts, and modern reason, with its own peculiar obscenity, grotesquely converge. The organic forms in Giants and Dwarfs, many of which are deformed—they are grotesquely mutated and are thus crimes that nature commits against itself—suggest that it is a garden that has gone to hell, as the barren, earth-brown coloring that pervades the fresco suggests. It is also worth noting that in Law and Order: Special Victims Unit a psychiatrist often appears, functioning as a sort of deus ex machina analyzing and evaluating the psyche of both victim and victimizer. Zansky is also psychologically minded, as his dream imagery makes clear. His

knowledge of psychoanalysis implicitly informs his art.

The predatory creatures proliferate in Bosch’s Triptych of the Garden of Earthly Delights,

Temptation of St. Anthony Triptych, ca. 1500–05, and the Hell, pictured on the right wing of the Hay Wain Triptych, ca. 1490–95. They are bizarre hybrids of different animals, many from different species, making them all the more grotesque and monstrous freaks of nature, suggesting that nature is inherently freakish—a reconciliation of opposites made in emotional hell. These creates reappear, however transformed, in Zansky’s tour de force series of ink and acrylic works, punctuated—punctured—with screws, as though to suggest how “screwball” they are, and as though to drill into the depths beneath the surface, perhaps suggesting the geyser of unconscious meaning that suddenly erupts from it. Among them are A Five Year Plan, Scalping the Indians (subtitled Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry), After the Flood, The Great Monster Rubenstein, and Tricks with Fire, all 2008–09. Texts appear in many of the works, as though to make their point clear—texts that hover in the air above the weird insect-like figures, like the thoughts that appear in balloons above cartoon figures, and like the texts that appear in medieval manuscripts and paintings, making the meaning of the image unmistakably clear. The

words Max J. Friedlander used to describe Bosch’s works readily apply to Zansky’s ink on paint works: “terse sharp lines” on “thinly applied paint,” suggesting the handling of “a carver in relief.” The screws make for a relief effect; the works in Giants and Dwarfs are also partly in relief, partly flat, suggesting a fusion of three-dimensional terrain and two-dimensional map, that is, textural literalness and conceptual invention—more pointedly a fusion of self-conscious surface and intimations of unconscious depth. The creatures in Zansky’s Burnt Drawings, Studies for Giants and Dwarfs are even more grotesque and distorted, and those in the New Kingdom series, 2012, are totally “insane”—a sort of protean primordial ooze, perhaps in the process of evolving into definite, refined form, perhaps devolving into raw indefiniteness. Zansky’s return to nature, like Bosch’s, seems driven by the death instinct rather than life instinct, as it was in Impressionism.

Dürer’s Melancolia I, 1514, and Goya’s The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters, 1796–98, along with his so-called Black Paintings, stand between Bosch and Zansky. The bat in Dürer’s print reappears in Goya’s print, transformed into a predatory owl, which is multiplied seemingly ad infinitum. (The bat is quoted in a Manet print.) The wings of both the bat and the owls are spread in flight, but where Dürer’s bat remains fixed in the sky, high above the melancholy angel seated on the ground but holding a sign naming the disease from which he is suffering, some of Goya’s owls come down to earth, landing close to the sleeper, almost on top of him, haunting, threatening, and glaring at him with blazing eyes. The bat wings that hold the Melencolia I sign are derived from the batwings of the Spectre of Death in the van Eyck Last Judgment, suggesting that melancholy is a kind of living death. Dürer’s bat and Goya’s owls are the ancestors of the giant multi-winged bat-like bug—another Spectre of Death—that appears in Zansky’s Giants and Dwarfs. It is Zansky’s “Melancholy,” as it were, on a par with Dürer’s woodcut—a sort of visionary expansion of Dürer’s allegory, which, for Redon, epitomized melancholy and was “written according to line alone with its powerful attributes.” It is a version

of the great Beast, named Mystery, in the Revelations. For me Zansky’s Giants and Dwarfs is a kind of apocalyptic handwriting on the wall—a grandly apocalyptic vision worthy of the fame of Dürer’s series of Apocalyptic woodcuts, admired because they seemed like etchings.

The bat, owl, and bug are equally ominous, emblematic, terrifying: creatures of the underworld that is the grotto of the unconscious—for Zansky a sort of Platonic cave where unenlightened beings live in perpetual darkness, a dreamworld whose inhabitants are nonetheless startlingly real. Just as Dante passed through the gates of hell, leaving all hope behind—which is one way of understanding what it is to suffer from melancholy—but recovering hope when he finally reaches heaven after passing through purgatory. Zansky, in his “divine comedy,” has his Rimbaudian “season in hell,” exploring every dismal cave in it, feeling peculiarly comfortable with the strange creatures that inhabit them, whereas Dürer and Goya are only visited by them. They remain on the rational surface—Dürer’s allegorical figure is deeply sunk in thought, reasoning with himself, and Goya’s human figure is an Enlightenment man of reason (he temporarily loses his reason when he falls asleep, that is, becomes unconscious, and is plagued by mad dreams, with his inherent madness taking the ironical form of the judgmental owl, a symbol of wisdom, the opposite of madness); whereas Zansky knowingly plunges into the irrational depths, identifying with the alien creatures at home in them. It is not clear that he ever

reaches heaven, although the twisted tondo images, related to the American Panopticon, suggest that he reaches purgatory, still a melancholy place of suffering.

Zansky is also concerned with reason, as his Age of Reason series, 2009, shows—a more particularly modern technological/bureaucratic reason (as I have argued), symbolized by his American Panopticon, 2013, hell and purgatory in one piece. The authoritarian panopticon may be socially rational—an efficient way of turning irrational, lawless criminals into rational, law-abiding citizens—but it has a dehumanizing, melancholy effect on those it imprisons. They are damaged social and emotional goods—screwed up human beings. Some of Zansky’s figures are twisted like screws. Tightening the social screws on them may seem to straighten them out, but it screws them up completely. The panopticon is institutionalized paranoia, rather than a

therapeutic humanizing space. It is another kind of Platonic grotto—a holding pen for dangerous “animals in the dark.” For Zansky, all-controlling technological/bureaucratic reason, epitomized by the Kafkaesque panopticon, is a modern prison meant to reform rather than punish criminals, individuals whose anti-social behavior implies that they are social misfits. It is a place where every move they make isolated in their cells is observed by an invisible observer. They are puppets whose strings are pulled by a god-like puppeteer—actors always on stage in the theater of the absurd that is the claustrophobic prison. This panopticon produces depressing dreams, which is what Zansky’s nightmarsh pictures are. The distorted, sometimes fragmentary figures in The New World 5 and Echo 8, among other works in the Age of Reason series, are manipulated puppets, and the spectator of the American Panopticon is its manipulative puppeteer, suggesting we all have a place in Zansky’s grotesque panopticon. The surveilled and supervised and the surveiller and supervisor are interchangeable. In technological/bureaucratic society, we are all watchful and being watched by some anonymous eye—an indifferent eye that claims to make a difference. Supposedly guarding us, it imprisons us. Zansky’s American Panopticon is satiric theater at its tragicomic best. It is a devastating critique of American society. “All the world’s a stage,” and for Zansky the world of the panopticon is the strangest stage of all.

For me Nebuchadrezzar’s Dream, pictured in A Five Year Plan, 2008–09, one of the ink and canvas group of works, along with Philip of Macedon, 2012, one of the New Kingdom series, are basic to understanding the social critical aspect of Zansky’s art—his sense that society is crazy and drives us crazy. The emperors Nebuchadrezzar and Philip of Macedon were the epitome of hubris: it drove them mad and caused their downfall. It made them grotesque animals—often pterodactyl-like and with sharp teeth—which is the way we see them in Zansky’s pictures. Some have thought that the fantasy figures in the ink and canvas works are the crazy characters in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Let us recall that the young Beckett, with his distorted sense of himself and his body, began psychoanalytic treatment with Wilfred Bion, an innovative Kleinian psychoanalyst, suggesting that the figures have to do with what Klein called the paranoid-schizoid position. Are the two figures, seated opposite each other in Tricks with Fire, analyst and analysand, both playing with psychic fire? Is it the fire of hell, or the fire that Prometheus heroically stole from the gods, for which they punished him? Or are Zansky’s tricksters just blowing smoke? Parody is clear in the works—the figures are caricatures—but I suggest that it is finally a parody of power in all its destructiveness and self-destructiveness.

Nebuchadrezzar II (ca. 630–562 BCE), King of the Chaldean Empire (reigned 605–562 BCE), was “the greatest member of his dynasty,…known for his military might, the grandeur of his capital, Babylon, and his important part in Jewish history.” He conquered Judah (Israel), among other countries, capturing Jerusalem in 597, attacking it again a decade later, capturing it in 586, deporting its prominent citizens to Babylonia, and deporting the rest of them in 582. This is the beginning of the so-called Babylonian exile of the Jews; in Jewish lore Nebuchadrezzar is ambiguously pictured as “God’s appointed instrument whom it was impiety to disobey” and as a worshipper of the “dragon”—the bestial god Bel (sometimes interpreted as the “Whore of Babylon” of the Revelations). Many of Zansky’s figures are a sort of dragon, and his work has a revelatory quality. More importantly for the interpretation of Zansky’s imagery is that Nebuchadrezzar supposedly went mad for seven years. Hubristically overreaching—which is what imperialism is—he became mad. William Blake’s “Nebuchadrezzar” shows him in a mad state; Zansky’s work clearly has a “delirious,” delusional Blakean quality.

Philip of Macedon, another hubristic imperialist, went mad in a different way. By 339 BCE he dominated Greece, preparing the way for the conquests of Alexander the Great, his son. Philip was a “subtle, pliant, patient, calculating diplomatist, master of timing in politics and war,” but “he ended his life in a tale of irresponsible incompetence.” “His love of drink and debauchery, and his wild extravagance with money” caught up with him when he led his “grand army into Asia” in an ambitious attempt to conquer all of it. He was not equal to the aggressive task; he was overambitious, suggesting that his grandeur had become delusional, which “fizzled out” because he lost control of himself. His hubris caught up with him: he was brought down to earth by his instincts. Surrendering to them, he became self-defeating, and with that could no longer lead his army. Over-indulgence—excessive pleasure—had made him peculiarly mad: he had in effect lost his reason. It is madness to challenge the gods by attempting to dominate and control the world they created, as though absurdly believing one created it by conquering it, making one as great as the gods who did. Philip showed his madness when, “during a procession, [he] set his own statue among those of the twelve great Olympian gods and was assassinated shortly afterwards in the theater.”

Nebuchadrezzar’s Dream is, in a peculiar way, the American Dream, which is why I suggest that for Zansky the imperialism, hubris, and madness of Philip and Nebuchadrezzar are metaphorically America’s. They too had America’s unrealistic sense of “manifest destiny,” which is why they were destined to be defeated. I regard Zansky as a prophet of doom, all the more so because his work has biblical grandeur.

http://michaelzanskyoverview.com http:/www.michaelzanskymonotypes.com.