Jasper Johns Mind/Mirror

Curator Carlos Basualdo & Art Theorist Ella Levitt

Now that we are collectively coming out of two years of pandemic induced pandemonium, what can art do, for individuals and society, at this sensitive-- or any other time?

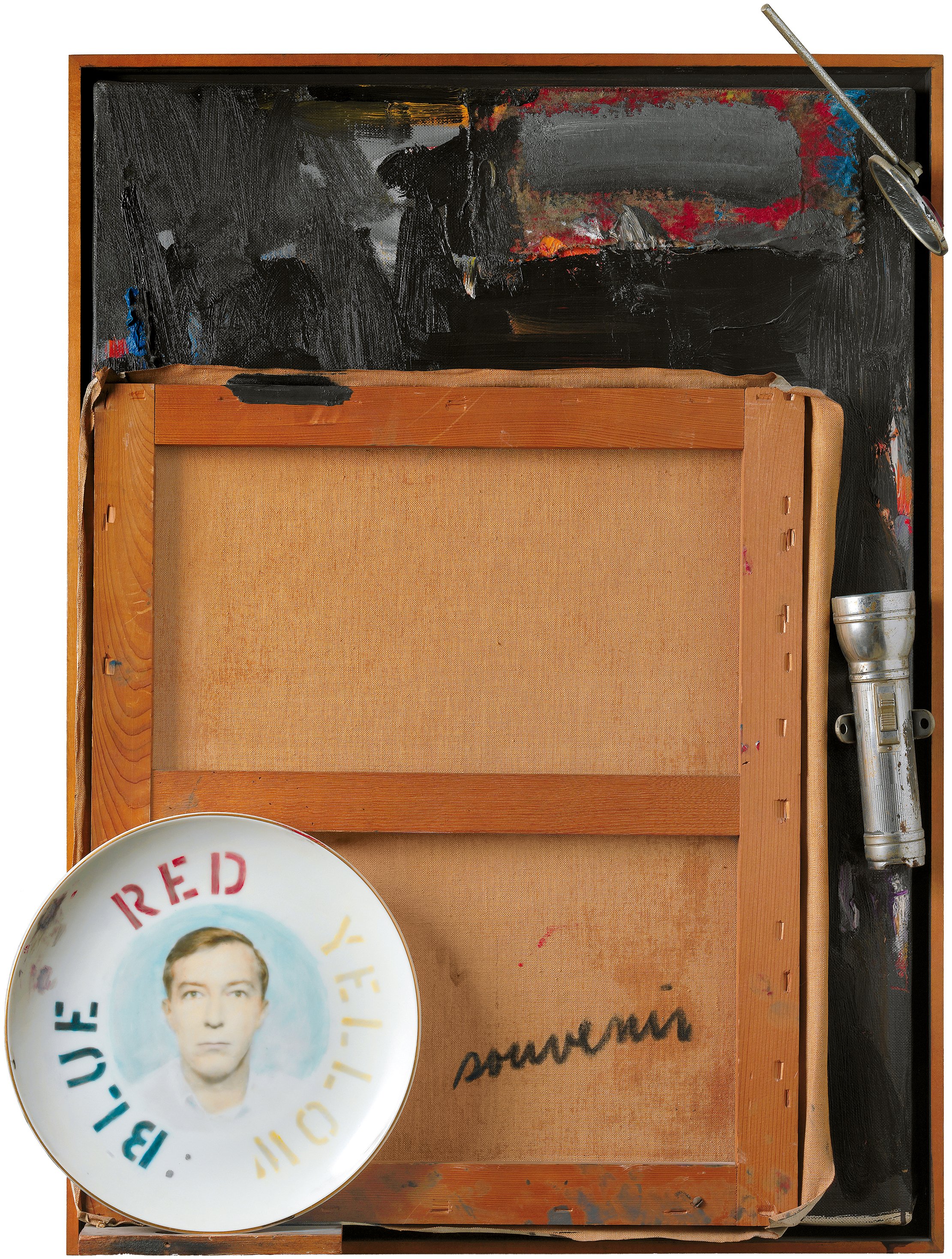

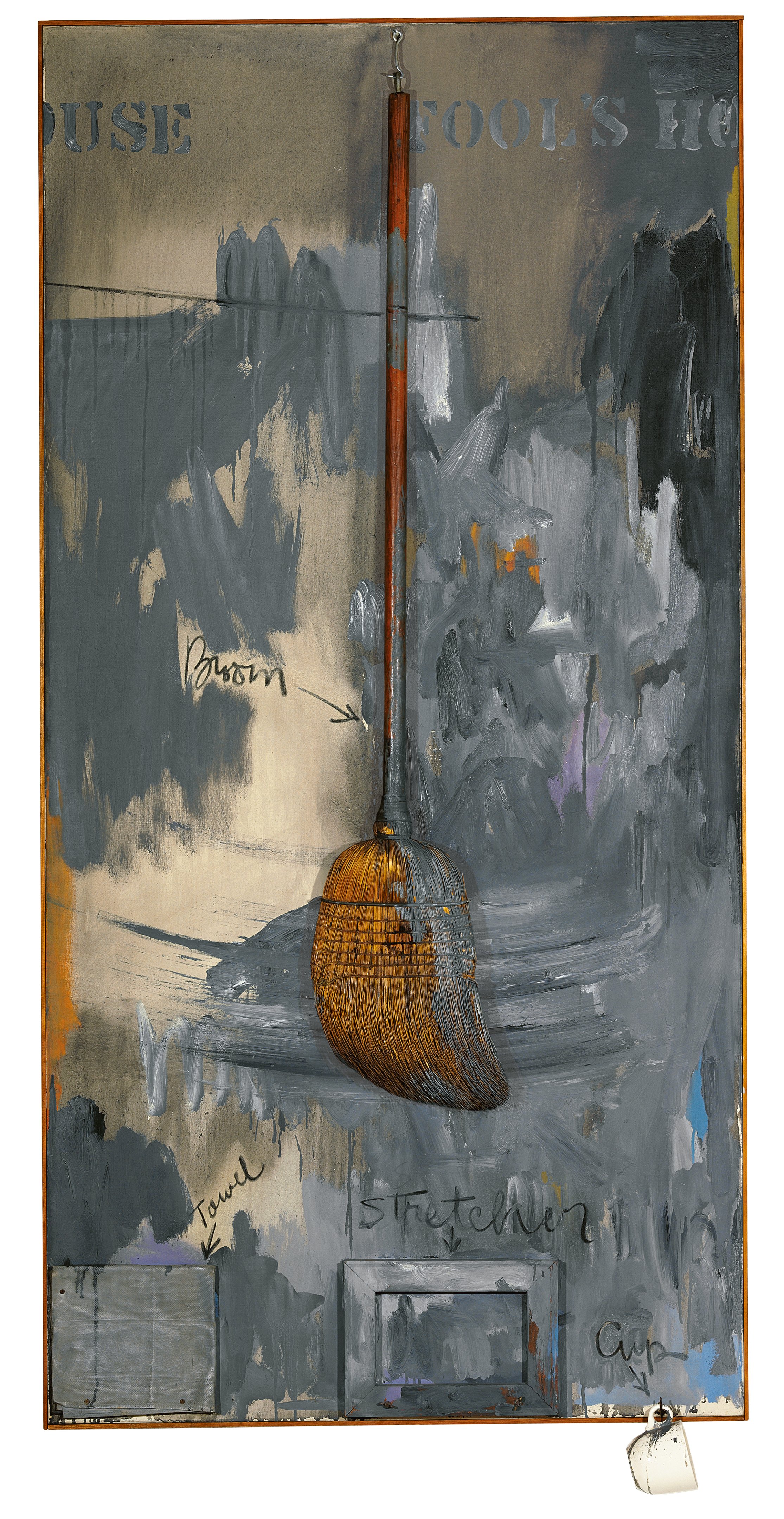

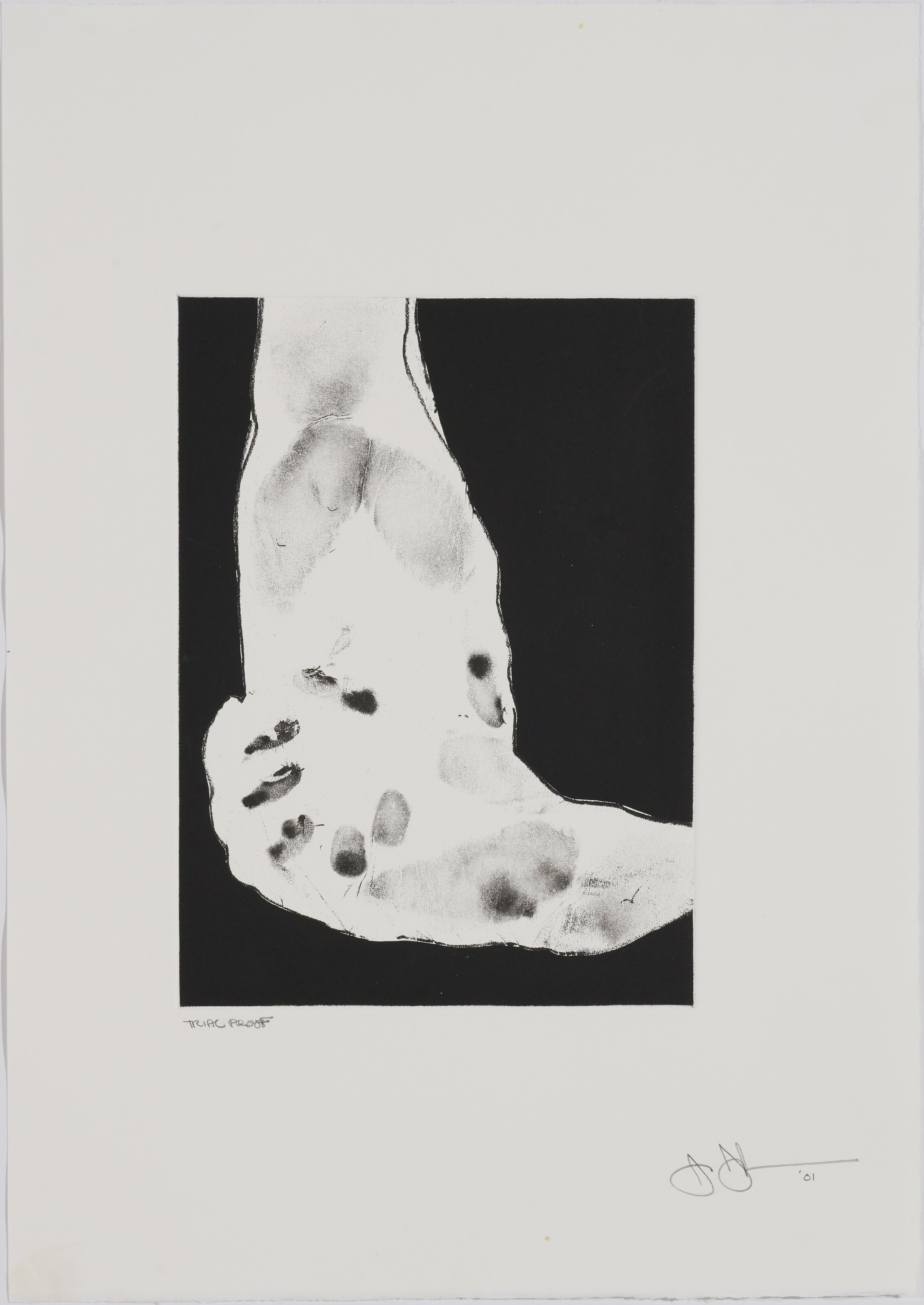

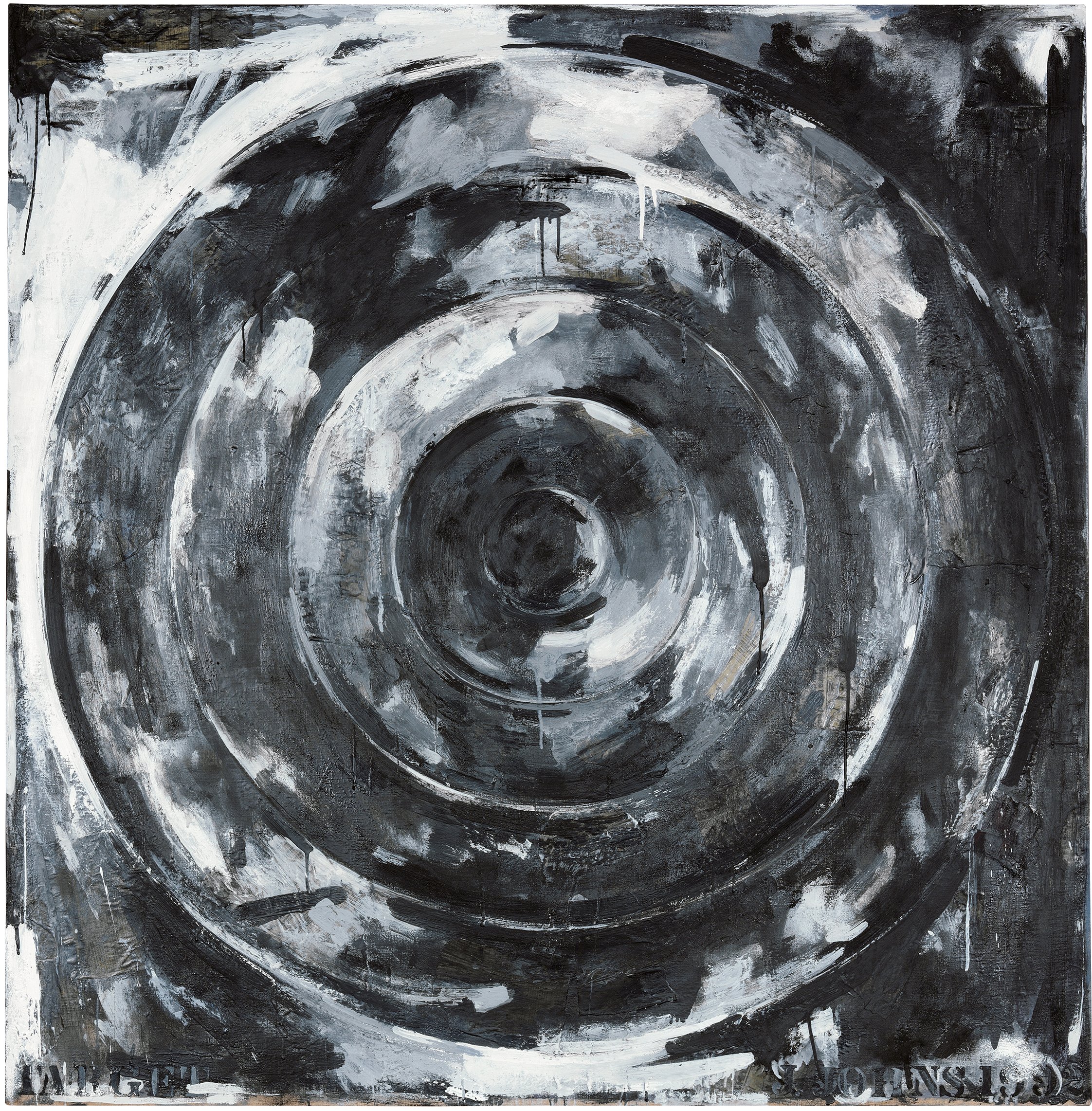

This fall, curators Carlos Basualdo and Scott Rothkopf unveiled a collaborative re-framing of Jasper Johns’ oeuvre as a show in two parts at both the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, both formidable institutions in the History of Art, but with very different scopes, histories, audiences and vibes. Ella Levitt recently caught up with Carlos Basualdo to explore how this show, Mind/Mirror, reveals its, and our, reality as parts of a whole, that is, individuals in society, concise art works and life-work, symbols and meaning-- including the unstable relationship between perception and truth, in service of this moment, situated in eternity.

Ella LEVITT: First of all, I want to congratulate you. This is a monumental achievement for you personally, and for the museum and for Jasper. I see it as a moment of celebration and along with that, reflection on how you got here. I thought to begin by asking you to tell us a little bit about yourself and what you were attracted to about working with Jasper. I wonder if you could share how you originally got involved with him and how the concept of this exhibition, you can even touch on the fact that it's two exhibitions, two locations, how this whole thing kind of came to be and evolved.

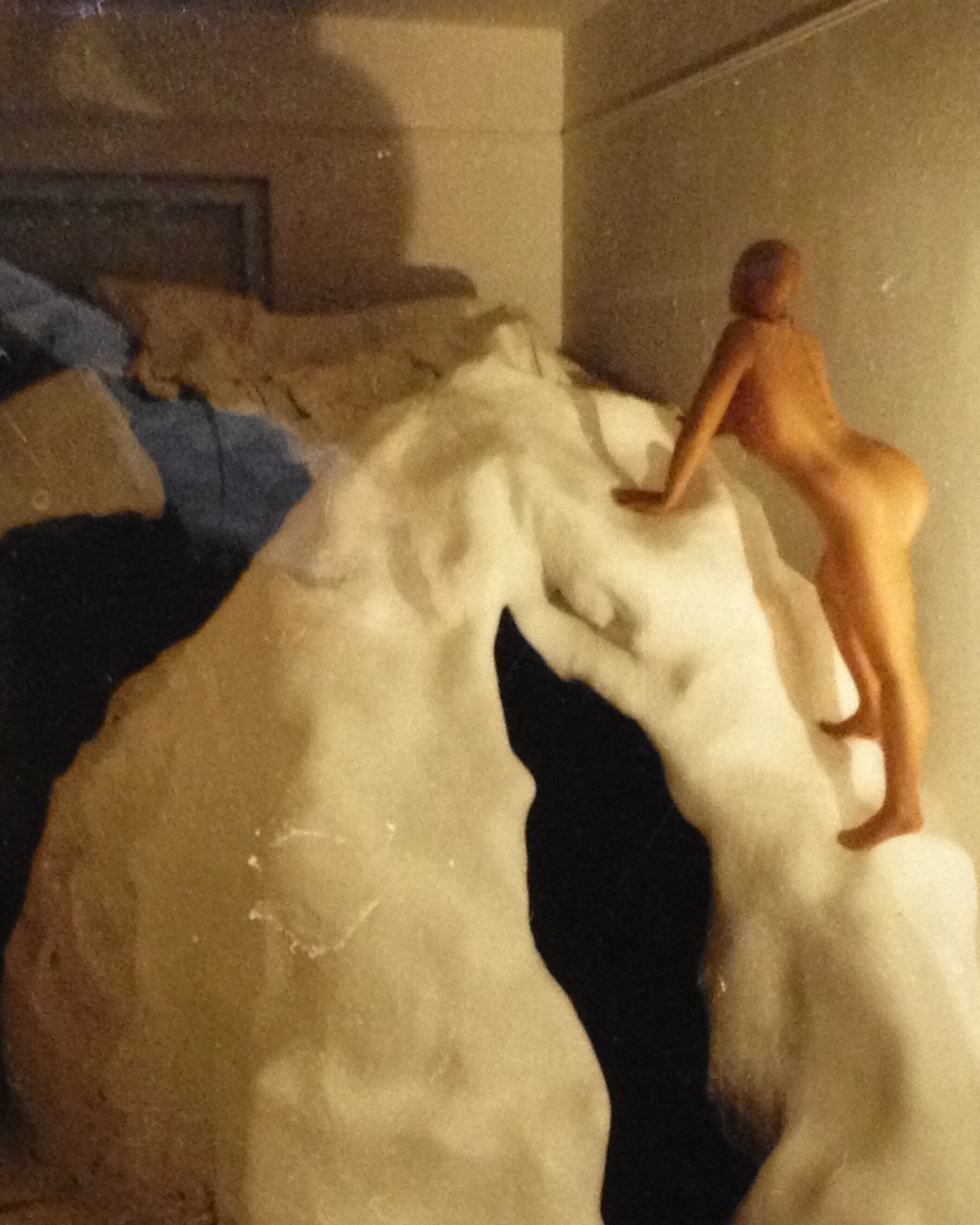

Carlos BASUALDO: I've been working at the museum since 2005. I was an independent curator before that. The Philadelphia Museum is, in the world of modern and contemporary art, best known for its Duchamp collection. As you know, we have the largest collection of Marcel Duchamp that there is, including The Large Glass and Étant Donnés. In some ways, the holdings of contemporary art have always gravitated in relationship to the Duchamp collection. When I first came to the museum, besides Duchamp, and Brancusi -there are rooms dedicated to each of them-, there were two other rooms, now there are four, dedicated to living artists, one was Cy Twombly’s Fifty Days at Iliam, and the other was a room with a collection of works by Jasper. Later on I learned a little bit about how that room came into being. It was part of a very long conversation between Johns and the museum that truly started when he visited the museum with Rauschenberg in ‘58, to see the Duchamp works in the Arensberg collection. Later on he befriended Anne d’Harnoncourt who was the curator of 20th Century art at the Museum in the 1970s. She would then become the director. And in the year 2000, Ann Temkin, who was my predecessor as a curator of contemporary art, installed the (Johns) loans that have been at the museum for decades in a single dedicated space.

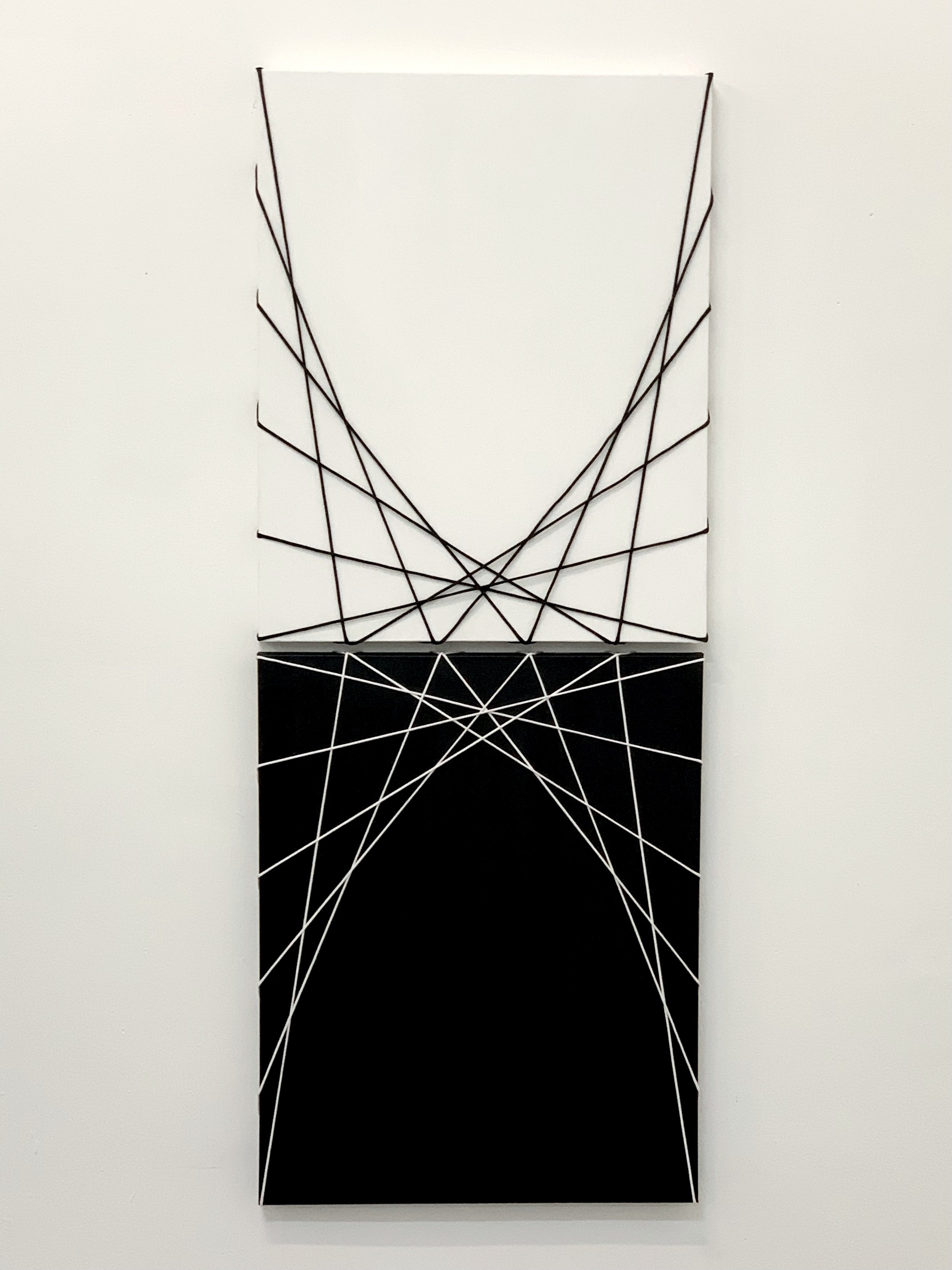

So in a way, Johns and Duchamp were very strong presences in the museum before I arrived. I always say that when Anne realized that she was not going to fire me, the first thing she did was take me to see Jasper, and it’s now been many years that I've been visiting him regularly. Now, I knew that Scott Rothkopf from the Whitney was considering the possibility of doing a Johns show, my wife had introduced me to him years ago when she was doing a postdoc at Harvard, and I was doing research on the history of exhibitions. Knowing how important Johns is for Philadelphia, I reached out to Scott and I said, “I know that you're thinking about Johns. Why don't we do a show together?” And the first question was, well, so how do we do it? From the beginning it was very clear to me that it would be interesting to think about the show in relation to a mirror structure. I had been interested for a long time in thinking about exhibitions as forms that change according to what they display. And, truly the form of an exhibition can actually be conceived in many different ways, and exhibitions should probably change in many ways depending on what is on display. Because what I've been trying to imagine is an exhibition that in its very form tells us something about its content. And so in the case of Johns, the challenge was, from my perspective, to test if we could do an exhibition that in its very structure would tell you something about the way in which the artist goes about his work.

EL: Interesting. So the two location concept, is a way of understanding the work—or the way he works--

CB: Yes, definitely. The idea is that the exhibitions have a mirroring structure, which means that there is a set of rooms, in Philadelphia, that correspond to a set of rooms at the Whitney. That was one aspect of the show. And the other aspect was related to the way in which Johns conceives of the relationship between parts and whole. If you look at the early interviews, he talks a lot about that. So the idea is that each of these shows is a part of an incomplete whole. And you know, it's a whole in itself, but it's also a part of a whole, so, another element that is important for me, is chronology. In Jasper's work, there are certain elements that repeat themselves almost as if time repeats itself. There's a cyclical nature in the work. And that also happens in the structure of the show. So I think there are a number of elements—or structuring devices-, in the shows that have been chosen to resonate with what we can identify as structuring devices in the work.

EL: That is very cool. If I can shift a little, it’s interesting to think about Jasper as being so established in Philadelphia for decades already, absolutely canonical within his lifetime, but of course there's a lot of criticism about why or how things get canonized. I’m wondering about the value of the canon, in particular, Jasper Johns’ indisputably canonized works for viewers today.

I mean, I think it's noteworthy, that in 2021, this exhibition takes work that is so entrenched and centralized in the mainstream narrative of 20th Century Art History, and sort of remixes it in a way that feels relevant, engaging and not off-putting to a broad and critical audience today. Do you think this exhibition might critique or extend notions of the canon, or do you have any thoughts about how we should best relate to, or employ canonical works like these today?

CB: Yes, you know, the ideas about what constitutes the canon are constantly changing, right? So when the museum first received its collections of what we now call Modern Art, the Gallatin Collection first in the 1940s, and then the Arensberg collection in the 1950s, they were far from being considered canonical. You have to keep in mind that most of the artists collected by Arensberg and Gallatin were contemporary, you know, Picasso was still alive. Many people considered most of these works quite radical. And, in the context of Philadelphia, well it is, and it was, a very traditional place, so you can imagine the astonishment that some of his work produced when they first came to the museum.

And then, there is, you know, Duchamp. Now it's hard to think about Modern and Contemporary art without Duchamp, but you have to keep in mind that in the 1940s and 1950s that was not the case. Duchamp only became a little bit better known when Robert Lebel wrote the first catalogue Raisonne of his work and that was 1959.

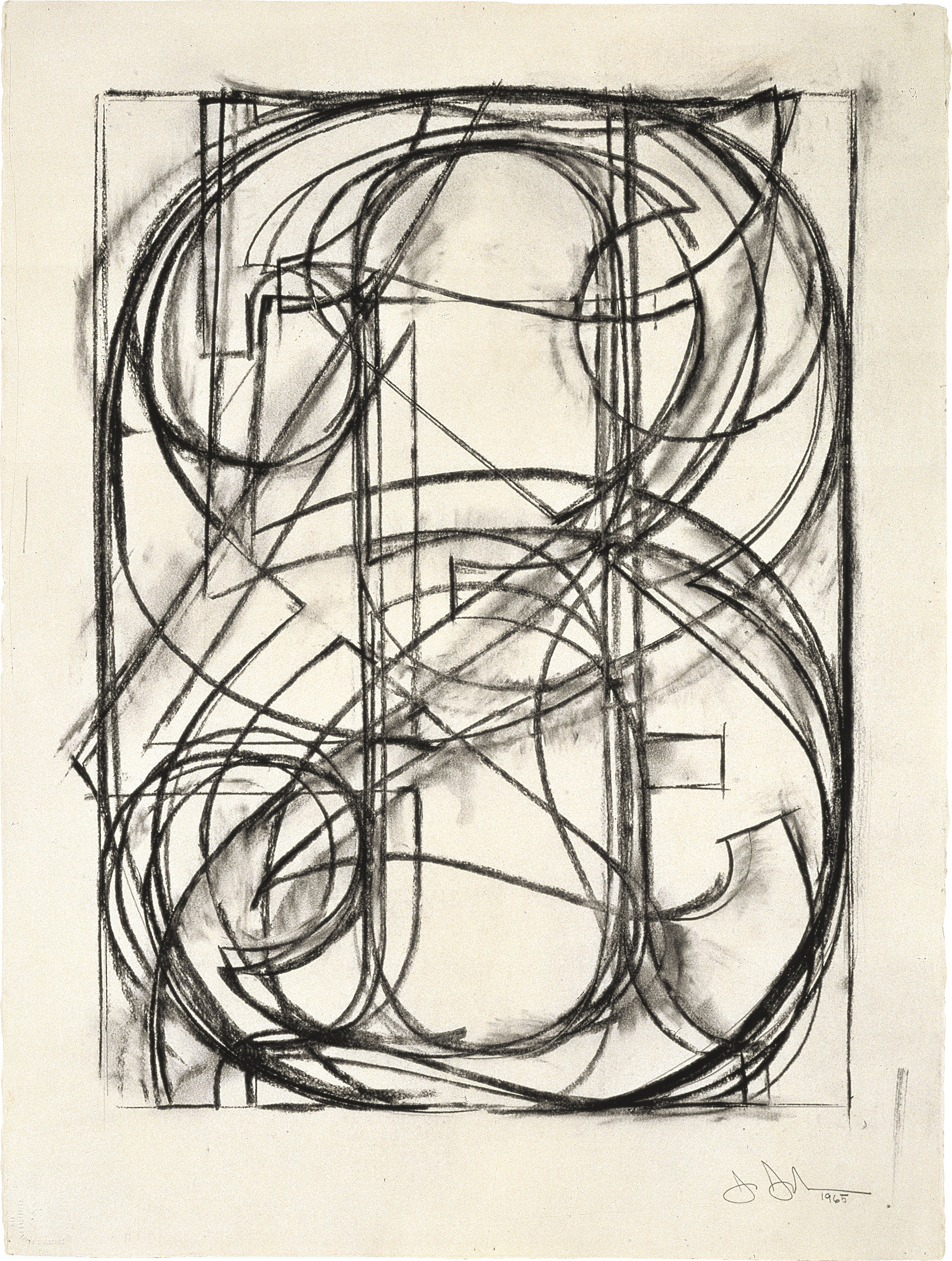

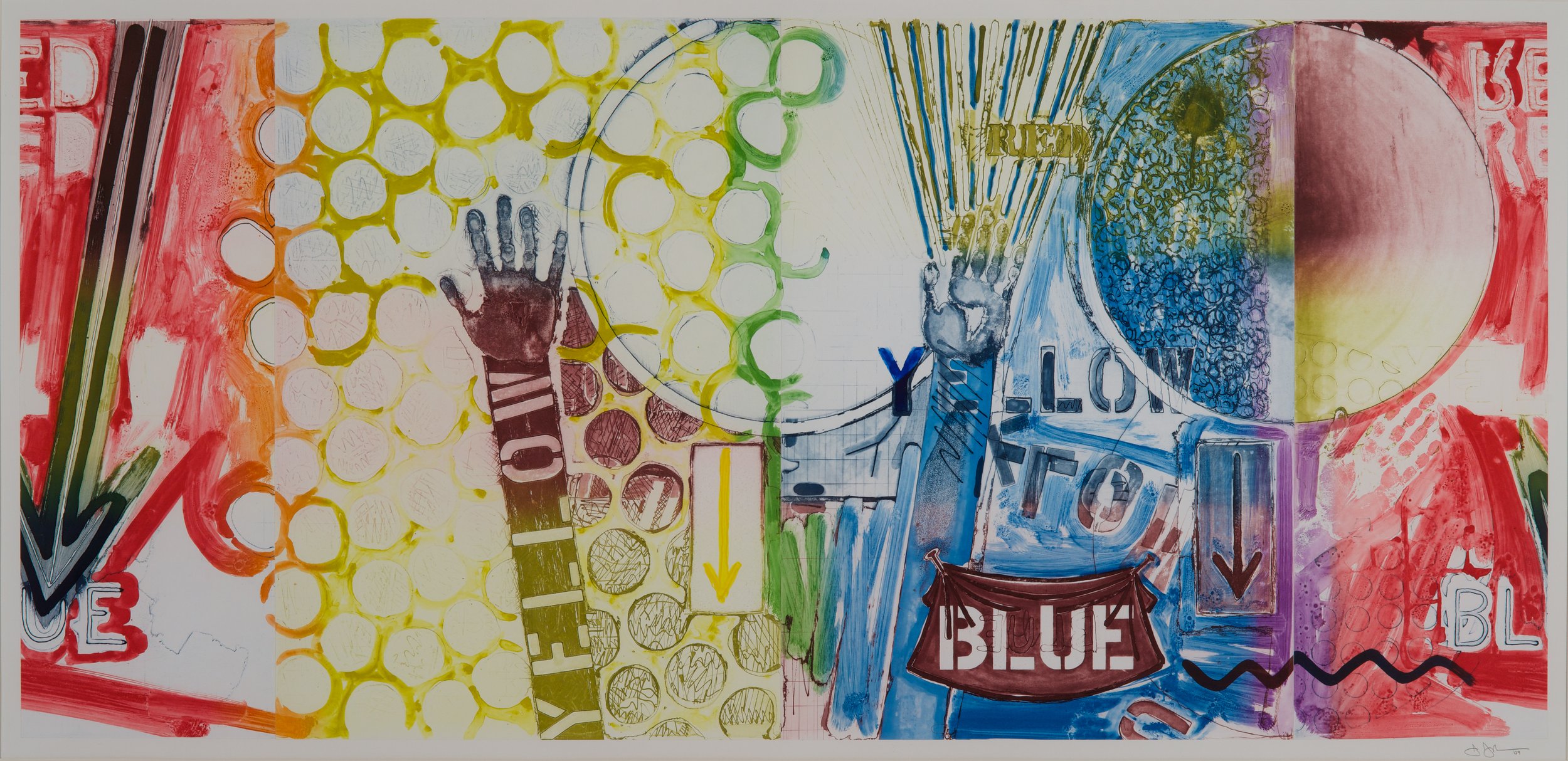

So, you have to consider that when the Arensberg Collection came to Philadelphia in 1950, Duchamp was not actually widely accepted. So I think you can see that in the history of the museum, this tension between what's canonical and non-canonical has always been at its core. In terms of myself and my own practice, before I came to Philadelphia I was not really working with what you would describe as canonical artists. When I first came to the museum, I had just opened a show called Tropicália (‘Tropicália, A Revolution in Brazilian Culture’), which was a show about Brazilian art, music, architecture, theater and popular culture in the 1960s, including people like José Celso, Lina bo Bardi, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Antonio Dias, before some of these artists had received institutional shows in the US. I’m interested, myself, in working with non-canonical artists in a canonical way, and with canonical artists in a non-canonical way. I believe this show of Jasper Johns has some of that quality, hopefully in regards to the premise of the show and the ways in which it disregards the traditional hierarchy of mediums, or even the very notion of what constitutes a finished work of art.

EL: I guess the question really is why is Jasper Johns relevant now? I mean, people come to the exhibition and feel like there's something new that's happening, even if they’ve seen the works in books and reproductions, so much, to the point of being almost invisible in popular culture.

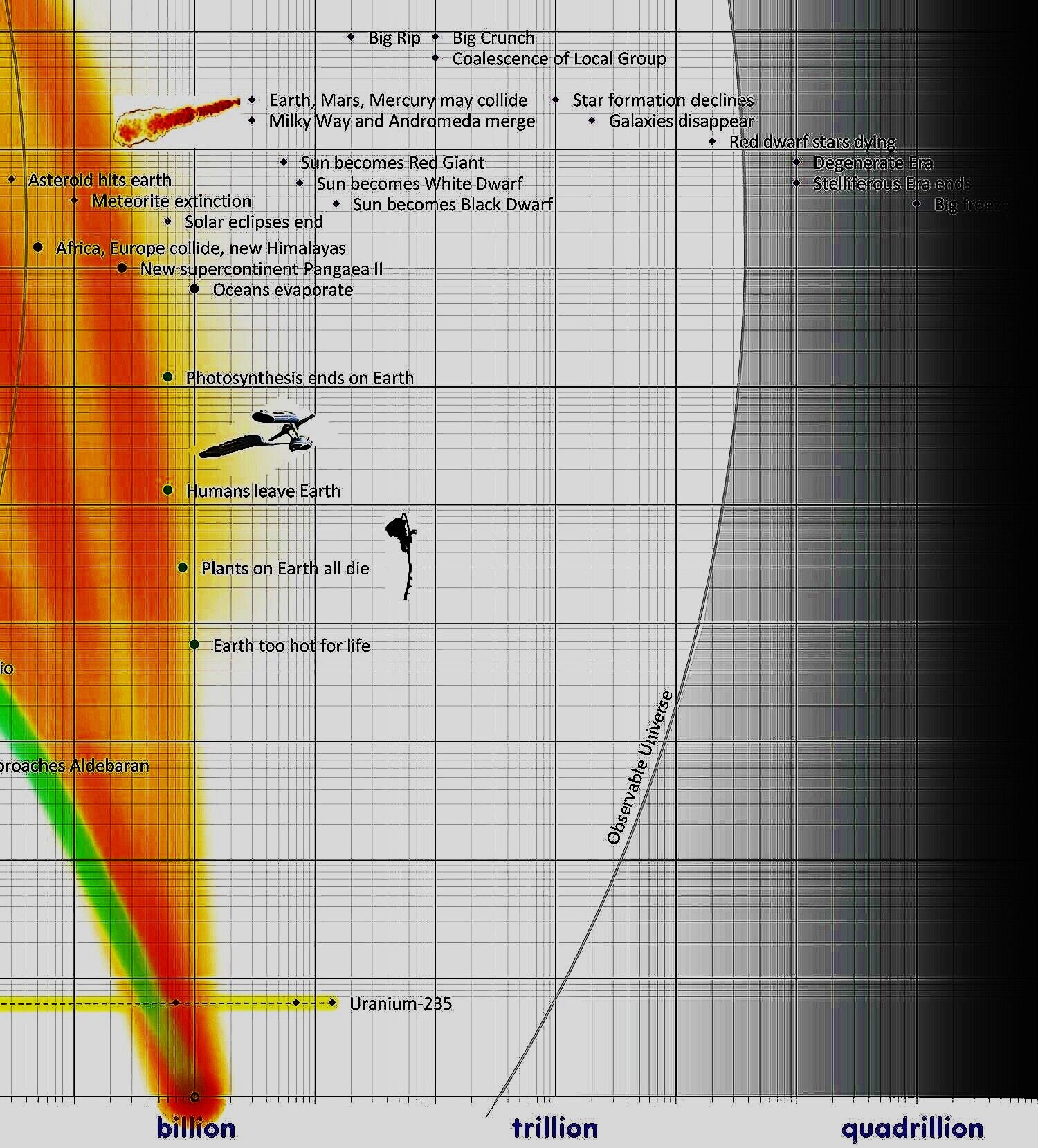

CB: Yes. I tend to think about that in two different ways. We recently had that conversation online with Scott Rothkopf and Ann Temkin, and she was referring to some of these elements, like the incorporation of works on paper and the disregard for the boundaries between mediums. Ann mentioned that it seems to be a very contemporary approach to the work. Scott has said many times that he was interested in presenting Johns in a way that would be interesting to a younger audience –even though I'm not sure I think in those terms. I do think that the work is extraordinary, and maybe because I am working in an encyclopedic museum, I tend to think of the work in the context of a larger arc of time. When you situate Jasper's work in that larger arch of time, it becomes extremely urgent and relevant to consider. That might have something to do with the way in which I think of time… I believe that everything that has been and everything that will be are somewhat expressed today. So any understanding of “today” needs to be problematized along those lines, from my perspective.

EL: As you were talking, I was thinking for a second, if you would consider Jasper Johns to have been ahead of his time when he was working in the fifties and sixties, but its sounds like what you're saying is that Jasper Johns is truly beyond time, especially when you situate it in an encyclopedic museum in this way.

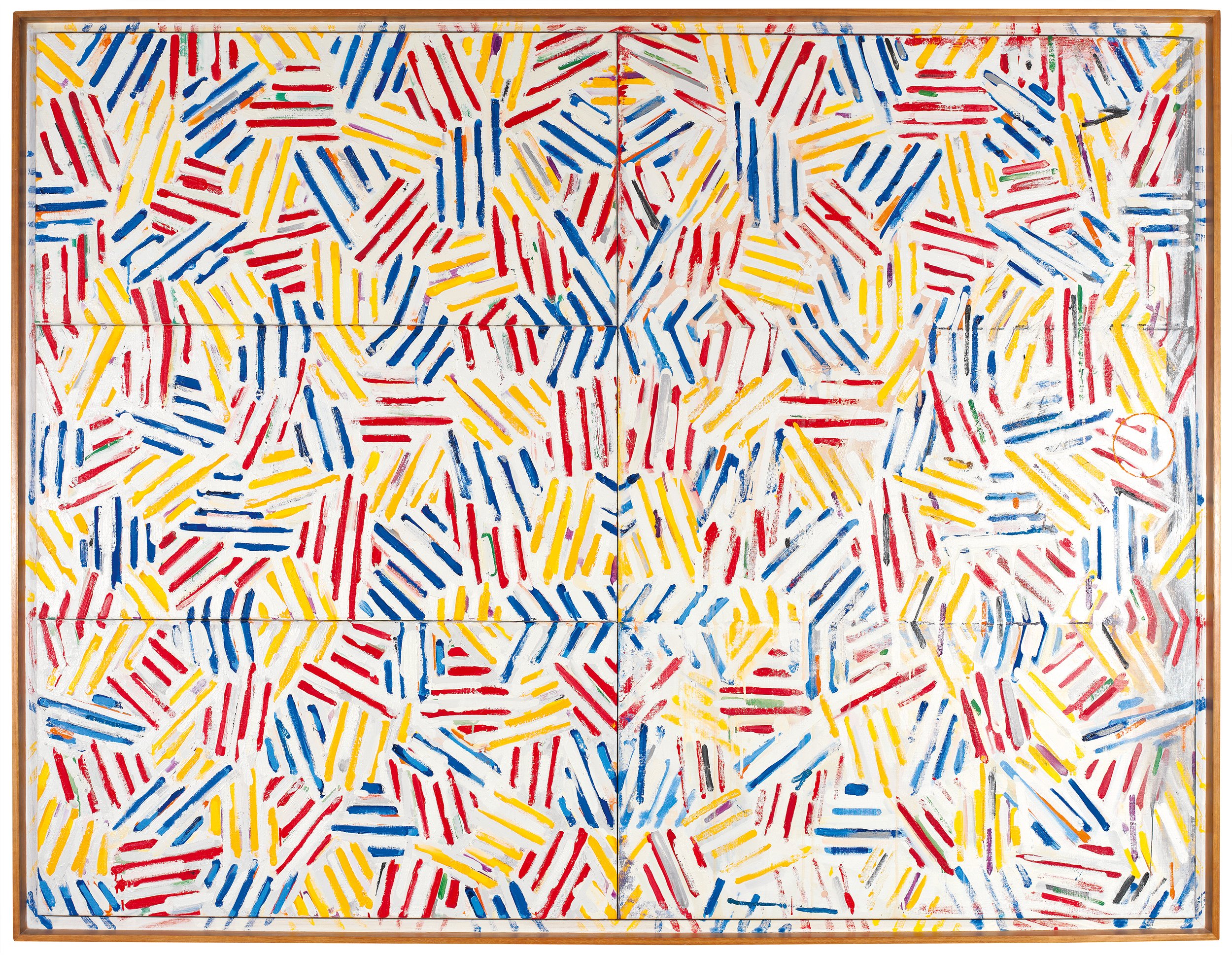

CB: Well, not exactly “beyond time.” The work definitely comes out of its time, but I think that there are many things in the work that you can describe as indeed very timely and closely related to the context of today. I think that the insistent blurring of boundaries, the fact that the meaning in the work is constantly being suspended, the gap that it persistently identifies between perception and truth, the fact that the work interrogates the very possibility of associating images with meaning once and for all.. It is very possible to think about those issues from where we are now or from the place where the culture seems to be, or at least where the culture in this country seems to be. But in general it is complex to try to locate art in time, because I think that as much as great artists belong to their time on one hand, they truly don't, on the other.

EL: One highlight that I associate with your body of work, is the Bruce Nauman neon from 1967: The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths, that belongs to the PMA and you included in Venice. I do feel there’s something mystical at work in Johns, and I’m wondering if you see something revelatory that Johns is guiding us to see, along these themes that you’ve touched on already?

CB: Well, there is a quote from Robert Filliou that Phillipe Parreno, a friend of mine -you know, he's a fantastic artist-,, always mentions: “art is what makes life more interesting than art.” I totally agree with that. Yes, I think that art is what makes life more interesting than art. So if art is interesting it is because it makes life more interesting, for sure. That’s why the question of its timeliness is so relevant. If it's going to be interesting, it's got to be interesting now. So the show is definitely not made to settle scores with the past, it’s made so that it can hopefully provide tools for people to think about themselves now.

EL: In thinking about how you might hope the public interacts with the work or in terms of their experiences, do you have any kind of expectations or goals in terms of desired interactions, and how the works might come to life?

CB: I like to think of the experience of an exhibition as a bodily, grounded experience. I always approach installations with that in mind, so that the meanings of the show come through the movement of the viewer. You make sense of the show through the movement of your body.. This is very much part of the way in which I think about exhibitions. The show in Philadelphia is very much based on that perspective, right? So there's a choreographic element in exhibition-making that for me is very important.

EL: I think we agree on the value of embodied experience, and that this is part of the transformational potential of encountering art objects, in real life. For me, this is the ideal, or highest goal of what art can do for individuals and society. But there's also a certain irony about the fact that these works were radical a long time ago, and have now become totally established, that is, blue chip investment objects of high market value, kind of abstracted from their materiality, almost the way NFTs can be bought and traded. So, in thinking about notions of value, how do you see the relationship between market value and say, spiritual or experiential or instrumentalized value? Is there a connection, or correspondence at least, between the economic value and the unquantifiable value of what the works can offer for the viewer, in terms of learning or spiritual enlightenment? Do you think high market value works do more for the viewer, or is it random?

CB: Economic value is attached to meaning, right? I believe that in Jasper's work meaning is constantly suspended. I think that makes it so that there is no ultimate key to the work. One of the things that was important for Scott and for me was to try to recall, to recover the element of surprise in the work. I mean, what did people feel when the work was first seen? That's something that you always try to do with work that has received so much public attention, because in some way, when a work becomes iconic, it almost means that it becomes invisible. So what you try to do is to restore the visibility to that work, and I guess you can only do that by providing it with a certain visual context.. That was very important in this case. We wanted the viewer to be able to see, as much as possible, the work under a different light.

EL: I think this was very successful. It is true that in the room with the maps, and the nightmare room and these kinds of things, the context definitely becomes a journey where you're led to see things in a different way. And I think that probably one of the huge successes of the exhibition is the fact that the works look new. They truly do, even if you've seen them in textbooks a million times, it's different confronting the maps and the flags and these kinds of things in their embodied form, versus a slide show. Materiality really does become a subject, and as you say, sort of reminds the viewer of our own materiality and so-- what about the fact that Jasper is 91 years old. Did it feel like there was a sense of mortality looming over the exhibition, or any of these darker themes, or, how does that connect to the right now-ness or the urgency of the exhibition?

CB: There's a section of the show that is called “Elegies,” and Scott was very keen on emphasizing how much Jasper seems to be thinking about issues of mortality in the new work, and he definitely is. But the truth is that the first time that the image of a skull appeared in the work was in 1962! He has been thinking about mortality for a very long time... Mortality, the disintegration or the fragmentation of the body, the impossibility of conceiving of the self as whole… Ultimately death is the dissolution of the self, at least that’s the way in which we think about death in the West. And so one can say that the dissolution of the self is something that has been part of the work from the beginning. You know, the work has always been about a self that doesn't seem to be able to imagine itself as whole. So I believe that one needs to qualify the presence of imagery that we would normally identify with death in the recent work. Instead,what I see clearly in the recent work is that it has become very concentrated and it's almost like a manifesto of itself. It sort of explains to you, step by step the way in which Johns has always worked. One example is Regrets, the series of paintings that originally started with a photograph that John Deakin took of Lucien Freud posing for Francis Bacon. Freud appears sitting on a bed in this photograph that was found wrinkled and torn on the floor of Francis Bacon’s studio. What you see is a man, a middle-aged man on a bed grabbing his head, in what seems to be deep lamentation. Now, if you look at other photographs from the same series, you realize that he's just combing his hair. That's a very recurrent trope in Johns, what you see is not what you get, right? The Ale cans look the same, but when you hold them, one is lighter (empty), the other is heavier (full). There is a clear interrogation about the relationship between perception and truth. But then Jasper traced the image in the photograph and duplicated it, mirrored it, what seemed to appear is a skull dominating the composition. So this is death. But again, this skull, or what appears to be a skull, is an image that emerged by chance, right? And then the title, it's called Regrets. So you have the perfect storm here. You know, there is a man, a middle-aged man, holding his head in a bed, the skull dominating the composition, and it is titled “regrets.” But “regrets” is a stamp that he used as he received so many invitations for events, he made a stamp that says “Regrets, Jasper Johns.” So there's obviously a tongue in cheek aspect in the work, and there's a distancing that suspends the drama that seems to be at play in the composition. The question is, is this about emotions deeply felt, or is it a sort of theater play, in which feelings are artificially activated by the work? I would say it's both. Maybe “regrets” simply means that the artist excuses himself from making that distinction at all!

EL: I feel that there's a performative element to all of it

CB: Yes, there’s definitely a performative aspect. There is a beautiful poem by Fernando Pessoa, the Portuguese writer that says, “the poet is a pretender, he pretends so perfectly well that he even pretends that it is pain, the pain that he is truly feeling” (in Portuguese it sounds much better…). I think that there's a lot of that, so we need to approach these ideas of drama, emotion and death with some caution. When I say that the work is a manifesto it is because, ,what happens in “Regrets” in fact happens all throughout the work. It's not that the work is deprived of emotion, but I do not think we can just say that the work is all about emotion.

EL: I think we can pause here. It seems like the perfect time to celebrate bringing these timeless works to life, in a fuller, more dynamic context today. I’m so glad we were able to discuss it.